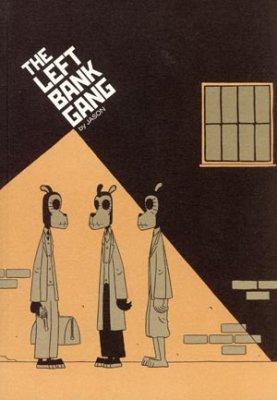

The Norwegian artist Jason (a.k.a. John Arne Sæterøy) draws dogs, cats, crows, and the occasional rabbit. They’re all anthropomorphic humanoids who sleep in beds and cook food, but they don’t emote and, in most of his books, they don’t speak. They observe their humdrum surroundings with a detachment bordering on existentialism, Buddhism, and pure malaise, making casual remarks like “I’m bored. Paris bores me. You bore me. Your friends bore me.” It’s a drab, plain-Jane world, but somehow, book after book, Jason manages to keep things exciting.

The Left Bank Gang mixes the Jasonian world with the Latin Quarter of 1920s Paris. The main characters include animal versions of Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Sartre, Joyce, Stein, and Pound, all converted into comic book artists struggling with their art and marriages. During an argument with Zelda, F. Scott Fitzgerald says, “Do you even love me anymore? You used to be the first one to read all my comics.” While having an affair with Sartre, Hadley Hemingway says, “I could have had anyone… and I had to go and marry a cartoonist with a little prick.” Ernest even calls Crime and Punishment “a good comic book.”

When the artists become tired of sitting in coffee shops all day, without any money, criticizing other comic books, they plot to rob a bank. Here, the narrative fractures, Reservoir Dogs–style, following each character through the heist as the situation escalates from a simple robbery to murderous rampage and betrayal. It’s a typical thriller plot, and Jason doesn’t seem interested in reinventing language or surprising anyone with visual fireworks. Instead, he retells familiar storylines with simple characters, in meticulous ink, for the sake of a purely entertaining comic-book read—something absent from most people’s lives since childhood.

Critics often credit Jason’s neat and dry aesthetic to the influence of Hergé (Belgian author of The Adventures of Tintin), but since his first book, Pocket Full of Rain (winner of the most prestigious comic award in Norway, the Sproing Award), Jason has shown himself to be a film buff. His speechless style references silent films, placing an emphasis on visually clear storylines; his minimal, often two-tone color palette echoes the bleak environments of film noir; almost all of his plots derive from the pulp film genres—Hitchcock thrillers, slapstick comedies, detective stories, and, in The Left Bank Gang, the heist film. The Living and the Dead, another upcoming installment in Jason’s film-based catalog, uses the template of the standard zombie story to plunge axes into heads and teeth into brains. However, with only seven lines of dialogue, most of which are old Hollywood idioms like “Don’t spend it all in one place” or “Hey there, big boy! Looking for a good time?” Jason maintains his typical deadpan irony throughout, turning the horror genre into a meditation on the clichés of day-to-day living.

In addition to all its filmic influences, The Left Bank Gang’s show-don’t-tell narrative owes much to Hemingway (a dog). Jason’s reimaginings of conversations between Joyce (a crow), Stein (a cat), and Pound (a dog) act as an homage to his masters. By turning these writers into comic artists, he blurs the mythology of the Parisian writers, the history of comics, and the history of literature in what may be an act of wishful thinking. Looked at in this light, all of Jason’s subdued, straight-faced stories seem actually to be exuberant celebrations of his love for film, art, and literature.