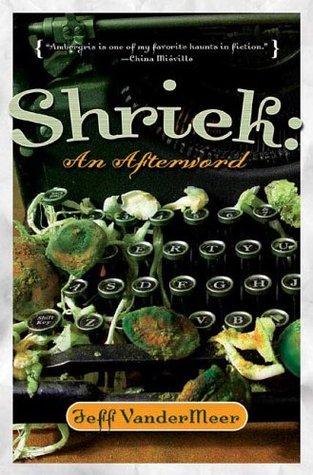

It’s not clear what obsesses Jeff VanderMeer more, mushrooms or books. Both appear on almost every page of his new novel Shriek: An Afterword, in which disgraced historian Duncan Shriek seeks to uncover the mystery of a race of mushroom people with mysterious fungal plans, who lurk below the surface of the moss-covered city of Ambergris. VanderMeer’s previous novels are part of a fantasy sub-genre, often categorized as the New Weird. While Shriek certainly contains fantasy elements, it doesn’t fit into any strictly delineated genre. There are more ideas here than flights of fancy; VanderMeer owes more to Borges than Tolkien.

VanderMeer conjures a neo-Victorian city which is as much a character as anyone in the novel. It provides a perfectly decadent setting for its melancholic inhabitants, who are made more real, and sadder, by the impossible strangeness of their home. Duncan’s art-dealing sister, Janice, narrates the epic story of her brother’s quest. Together, they negotiate doomed love affairs, drug addiction, lust, suicide, war, and the writing and publishing of books. Her voice is formal, but it throbs with gloom and mustiness. The stiff prose only makes the appearance of so much fecundity unsettling.

Duncan is consumed by his quest to understand the “gray caps” who haunt the city’s history, but is himself haunted by the early death of his historian father and by an old and career-destroying love affair with a student. During the course of his historical investigations, Duncan becomes infected with a ghastly virus that slowly takes him over. As he tells Janice, “One day I will dissolve into the world, will become a gentle spray of spores, will settle on the sidewalk and on trees, on grass and soil, and yet still be—watchful and aware.” His search for historical truth is akin to his search for a love that will redeem him from what is, both figuratively and literally, a fungal disease.

VanderMeer’s fantasy vision is a hallucinatory incantation not just of mushrooms but also of literature. The names of books and their authors are invoked throughout the novel, which itself is a metagloss on this obsession. Janice supposedly records this story as an afterword to her brother’s book, The Hoegbotton Guide to the Early History of Ambergris. Shriek is also a sequel to an actual book of the same name, written by VanderMeer, and recently collected in a volume of his Ambergris stories, City of Saints and Madmen. Reading Shriek becomes practically vertiginous when Duncan himself annotates Janice’s text, appearing in brackets every few lines or so. Duncan comments on, argues with, defends, and mocks his sister’s attempt at explaining the twists their lives take. If it weren’t for all the mushrooms (often referred to as “fruiting bodies”) being smoked, eaten, stepped on, and breathed in, you would think that books were the fungi invading the city.

With fantastic literature, metaphor must have some mythical possibility, or it becomes literal, and merely silly. A man slowly turning into a mushroom works in Shriek precisely because the metaphor of fungus completely permeates the book. It becomes hard to tell what is a person and what is the growth and decay of the city, a city claimed by mushrooms: fungal underground inhabitants haunt it, spores cover it, and people are addicted to hallucinogenic varieties. But beyond that, the people themselves are more mushroom than they would care to admit: fleshy, capable of inducing madness, clinging to other people as if to the base of a tree, desperate for nourishment.