The 1915 film The Birth of a Nation is the wellspring of D. W. Griffith’s fame and infamy, a movie that is both technically pioneering and stinkingly racist, even for its own time. But Griffith made hundreds of other films, including a handful that are remarkably open and fluid in their racial sensibility. His Trust, a short from 1911, is a particularly magnificent example of how Griffith’s films sometimes worked against racial ignorance in bold and evocative ways, even as they seemed to reinforce it.

The film, set during the Civil War, focuses on George, a slave who rescues and shelters the wife and daughter of his master, who had died in battle against the Yankees. On one level, it is a compendium of early twentieth-century black stereotypes, most notably the ridiculous “happy Negro” (played in blackface by the Canadian actor Wilfred Lucas) whose loyalty is strongest to the people who oppress him. Yet in moments of unexpected tenderness between George and the colonel’s widow (Claire McDowell), His Trust somehow manages to undermine its own prejudices.

For instance: Just after her house has crumbled in a fire set by marauding Union soldiers, the widow stands dazed until George comes to her side and takes her hand, leading her and the child to his slave cabin. It is a small exchange and a small moment, yet at the same time an act of intimacy that suggests a mysterious wealth of feeling, as though for a few seconds the white actor playing the black slave understands something about the future beyond the camera. At this moment, the facts—that Griffith’s mother sewed robes for the Ku Klux Klan, that between 1909 and 1911 nearly two hundred blacks were lynched in the United States—seem to belong to some other history. All that registers is the human contact on the screen.

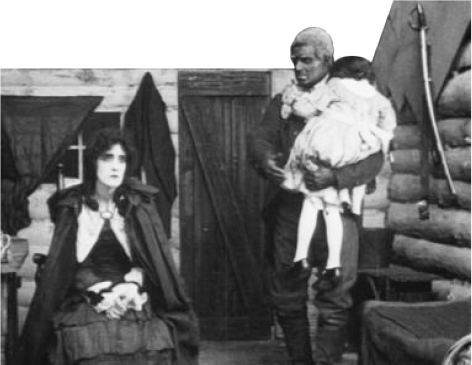

In the scene that follows, we witness the three characters in the close quarters of George’s cabin. He holds the sleeping child—the contrast between black and white could not be stronger—and gazes at the colonel’s widow. It is a portrait of a racially mixed family, black and white bodies close together not in the white house but in the black. Here it’s not just the togetherness that’s jarring but also the setting: while earlier we saw the opulence of the colonel’s house—the paintings on the walls, the elaborate mantle,...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in