Chapbooks are books in the way that zines are magazines: produced in small quantities, often lovingly, by hand, with attention to aesthetic concerns, and without any significant financial motive. They are not widely distributed and are often read only by a small circle of enthusiastic initiates already familiar with the author and/or their work. In the poetry world, where convincing a publisher to put out your book is like convincing a stranger to toss all their clothes out of an airplane, chapbooks are the currency of the young and the previously unpublished. But they are also the currency of established poets enamored with the brevity of a form which, like the novella, allows for a more compact mode of expression. Lynn Sukenick’s Houdini is a cycle of poems too short to stand alone as a book, but which expresses a complete poetic thought, perfectly suited for a chapbook.

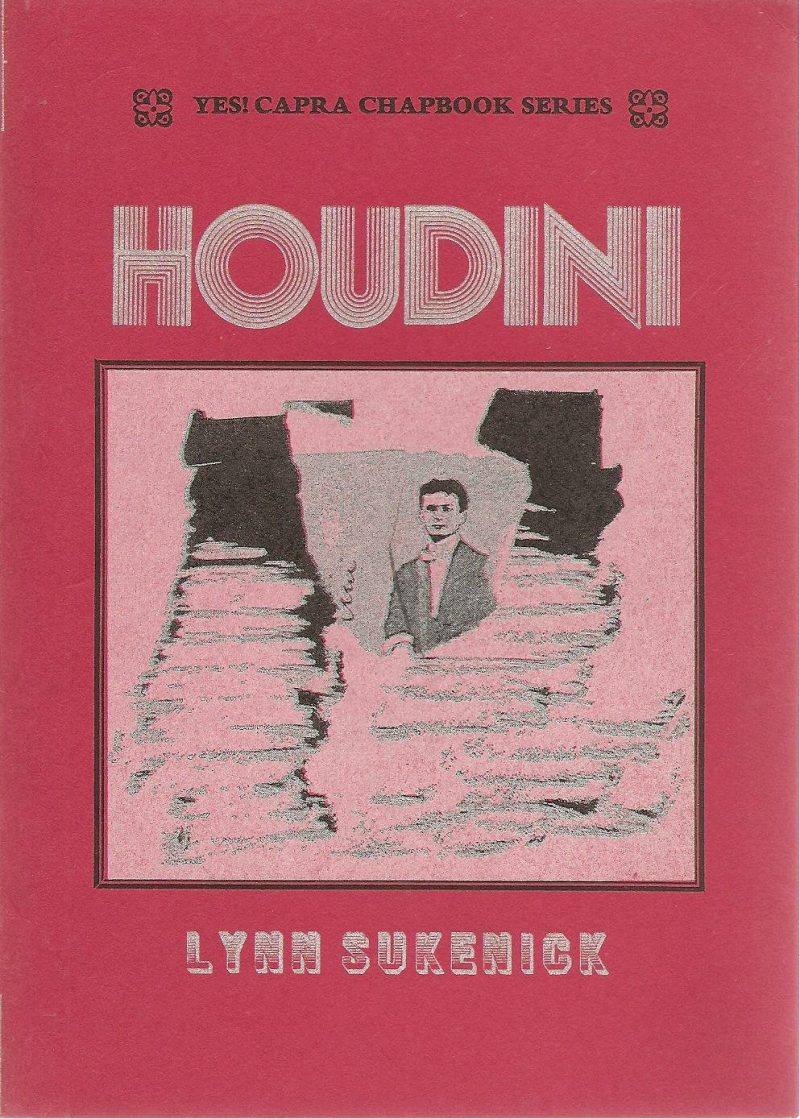

Houdini was published in 1973, as number fourteen in the Yes! Capra Chapbook Series, which includes such luminaries as Henry Miller, Anaïs Nin, Andrei Codrescu, Diane di Prima, and Ray Bradbury. One hundred numbered, signed, and hand-bound copies were each illustrated with Sukenick’s own black-and-white collages. It is a tiny thing, this pocket-sized book with red paper covers printed with silver and black ink. The poems inside, however, are anything but slight. Numbered one through twenty-five, they investigate Houdini’s inner life and the ways in which the poet identifies with a performer who “always started, himself, / what he meant to undo.” They go from deceptively simple declarations just a few lines long (“Hidden all over the world / are perforations / only he / could tear”) to longer, more complex poems that play with the idea of the poet as performer writhing in the bonds of language, an act Sukenick presents as both evasive and powerful. “Houdini’s / the brightest angelic vein / in the heavenly thunderlode. / As the sea kicks shelled animals back as beautiful vowels, / the consonants of their intestines gone— / he teases us / with pieces of chain; / the flickerings of his former shackles: / confetti, / popcorn, / stars!”

Poets often conscript cultural icons to help make meaning in tight spaces. Jean Valentine’s chapbook Lucy puts the poet in conversation with the earliest-known woman, and in Kiki Petrosino’s Fort Red Border (reviewed in this issue), Robert Redford stands in for the poet’s beloved. In Houdini, Sukenick uses the famous escape artist to conjure not only metaphors of entrapment and self-preservation, but also the expectations of a hungry crowd, in both the intimate sphere of the individual and the public sphere of the artist (“Houdini, I too / am uncomfortable, / shoulders up, in a high window; / below, the tiny pulse of a crowd, signaling for language”).

These poems self-consciously enact the performance of poetry. In number twenty-four, anagrams of Houdini take center stage, and Sukenick flips letters into almost-nonsense: “Hon Hun Ho Nido Din Don / Hod Nod / HID.” But this is not language play simply for its own sake. This is a nod to the power of the poet to transform language such that it either reveals or conceals her true self. By the time we reach the last poem, a dangerous longing has been revealed. We hear the voice of an artist and a woman yearning for freedom, for control over her own destiny, even if it might eventually prove fatal. “Though even / they numbered in the hundreds / and did hound him / and descended / this night of silence was what he needed, / and no nets under him.”