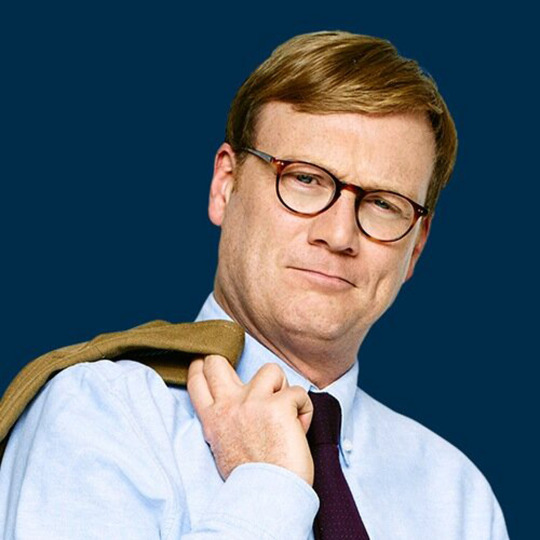

An Interview with Review Actor and Writer, Andy Daly

Andy Daly is an actor, comedian, and writer. He wrote and starred in two seasons of the Comedy Central series Review and has appeared in lots of movies and TV shows (Semi-Pro, Eastbound and Down, Silicon Valley, The Office, and Reno 911, to name a few). He’s also a stand-up comedian who has created a host of absurdly unhinged characters, like Dalton Wilcox, the Poet Laureate of the West who hunts vampires and mummies, and Don DiMello, the former director of the Radio City Christmas Spectacular who produces live, depraved interpretations of Disney films. Daly hosted his own podcast, the Andy Daly Podcast Pilot Project, released a collection of his character work on the album Nine Sweaters, and frequently appears on podcasts like Comedy Bang Bang.

While all of Daly’s work is hilarious, full of depth, and worthy of your time, Review is a thing of genius. Its main character, Forrest MacNeil, hosts a TV show (also called Review), where he reviews life experiences and reports back on their merits or dangers to the public at large. Unlike other sketch comedy shows, a narrative builds within each episode and stretches across the series, since MacNeil’s actions naturally impact the course of his life and the lives of the people he loves. Review ultimately deconstructs the antihero archetype from within the structure of a dark and absurdist comedy. It’s silly and it’s sad, and it will undoubtedly influence a generation of writers to come. Recently it was announced that Review will return for a third and final season, with a limited number of episodes, and Daly has announced his next project, an ABC pilot called Chunk & Bean.

I spoke with Daly about Review, what he learned from working with Amy Poehler, and the time his hero Hunter S. Thompson kicked him out of a party.

—Stephanie Palumbo

I. DON’T OPEN THE DOOR

THE BELIEVER: Review is about so many different things, but how would you describe the core, the heart of the show?

ANDY DALY: I think Forrest MacNeil is a guy who has come up with a way that he can matter in the world. He truly believes that he’s making an important contribution to society, and society will change for the better, forever, because of his efforts. If that’s what you believe, then no obstacle, punishment, or hardship that you inflict on yourself or anyone else is too great to achieve it.

What’s fun is that within seconds, any one of us watching this show can understand that he’s wrong. There is no great contribution, and nothing is being learned. To me, that’s the deliciousness of the premise. This guy is willing to give it all to something we immediately know is stupid.

BLVR: In a way, Forrest is paralyzed and unable to make his own choices. But at the same time, he’s made a choice not to choose.

AD: Right, or he’s willfully handed over control. In the early days, we talked a lot about that scene in Young Frankenstein where Gene Wilder’s character says, “No matter what you hear in there, no matter how cruelly I beg you, no matter how terribly I may scream, do not open this door.“

It’s such a funny scene and obvious set up. Forrest has done that to a large extent: he has gone into this show saying, “I will do anything anybody throws at me, no matter what it is.” He’s handed the keys over to Igor. He has surrendered his own free will.

BLVR: I see parallels to a type of addiction. He’s beholden to something that’s making his choices for him, and he’s losing all of the people he loves, one by one, as a result.

AD: We definitely have talked about Forrest as an addict. Not that he’s literally addicted to doing this show, but that his behavior is addict-like. We’ve spoken about his wife Suzanne’s attitude toward him—how do you deal with somebody who is more devoted to this other thing than to his own safety or the safety of the people around him?

BLVR: In an interview you did with Paul F. Tompkins, you said that when you were thirty, you quit drinking and adopted a dog, and that sacrificing for something else helped you—that being selfless made you happier than being selfish. Did your personal experiences inform your approach to the show?

AD: I can’t say the connection is one I’ve made consciously, but yeah, quitting drinking allowed me to be less selfish. My wife, who was with me when I was drinking a lot and is still with me now, thank goodness, would definitely say that one of the major benefits of me quitting drinking is that I have more time and focus for other people. There were times that I would be drunk and just leave a place by myself because I had an impulse and wasn’t thinking through the repercussions on others. But I haven’t drawn a bridge between the show and my own experience explicitly.

But the process is sloppy. It’s a soup of ideas that come from different places and mean different things to different people, and of course when you let it out into the world, it’s going to be received differently, but it’s all wonderful to me.

BLVR: Review is adept at dealing with controversial topics at a time when some comedians claim that “PC culture” hinders comedy. I read that you wanted Forrest to review getting breast implants but decided not to pursue it because it might be perceived as mocking a particular transgender experience. Do you feel responsibility to think through the implications of a joke?

AD: I have begun to wonder where the term “politically correct” came from. It’s such a horrible phrase, the notion that politics could be correct or incorrect. I feel like the original proponents of what we now call political correctness could not possibly have called it that. But really, at its best, what it’s saying is, “Don’t be a dick. If there’s an opportunity to not hurt somebody, don’t hurt them.”

But people don’t like to be told. For instance, your example of that piece where Forrest was going to get breast implants. It took me a little while to think it through, but I considered it from the perspective of the transgender community and empathized and realized: yeah, it would hurt. If some comedians don’t want to sacrifice certain jokes, that’s up to them. But they have to be prepared to look like a dick.

BLVR: Review never feels like it’s sacrificing any humor. In the review of racism, it just turned the joke on its head, so Forrest was the butt of the joke instead of his black neighbor.

AD: We really agonized over that review, but I think that was the key to cracking the piece. It opened up a whole other risk—is our main character irredeemably unlikeable? We’d rather risk that than to make a minority group the butt of the joke.

II. A STEP BEYOND REALITY

BLVR: Forrest is much less deranged than many of the other characters you’ve created – like Chip Gardner, the former game show host who’s campaigning to be the Honorary Mayor of Hollywood while also trying to bring about the rise of his dark lord Satan. They’re often ordinary guys with absurdly exaggerated, insane tendencies, but for some reason, I find myself feeling a sort of tenderness toward them all, no matter how evil they are.

In order for you to play any character, do you have to empathize with them at least a little bit?

AD: Oh yeah, that’s for sure, I think you do. I read an interview with the actress who played Nurse Ratched [from One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest], and she said she’d come up with an internal reason for why her character was the way she was. You can’t just think, “This person is a villain, evil and horrible.” You have to understand where they’re coming from, even if you think they’re wrong.

It’s also fun to play someone who seems evil and to reveal their vulnerabilities. When I played L. Ron Hubbard on the Dead Authors Podcast, he pouts and gets his feelings hurt. It’s super fun because it’s true. People manipulate other people and make them feel guilty. Monsters get their feelings hurt all the time!

BLVR: Do you think you’ll do more as L. Ron Hubbard?

AD: I do, though I’m not sure exactly what. It’s great fun to memorize somebody’s biography, and then liberally play with the real facts of their life and go a step beyond reality.

BLVR: You take him out of the real world and into the world of your characters, where he belongs.

AD: He does. Somebody said on Twitter, “If L. Ron Hubbard hadn’t existed, Andy Daly would have created him,” which is so true! He’s an occultist, a narcissist, and a criminal in all the ways that so many of my characters are, so he’s fun to play.

BLVR: Have you ever done stand-up comedy as yourself, without a character?

AD: I have, yeah. When I first got to New York, around 1993, an agent advised me to do stand-up, because at the time, stand-ups were getting development deals based on five minutes worth of material. I think I was okay at it, and I got some very good feedback from people, but I could tell that there wasn’t an onstage “me.”

There wasn’t a persona or an attitude that I could reliably write good stuff from. I am, like anybody else, full of contradictions and personality traits, and I don’t know which ones to speak from as a stand-up or what aspects of myself to ask an audience to identify with. It has always felt to me like a bit of a white whale, and I would love to crack it someday but I’ve never been able to think my way around it.

BLVR: You’ve stated that you over-prepare for live performances but not for podcasts, which surprised me. I would imagine that you’d prepare more for podcasts, since they’re recorded and will be heard by a larger audience.

AD: The feedback I hear about podcasts makes it seem like listeners are very forgiving of tangents and beats that fall flat and false notes, like people just enjoy putting on headphones and getting lost in the world of these characters. Whereas when you’re in front of an audience, man, you know if it didn’t work. I get very nervous and have a fear of failure that is much more profound than in the podcast world. I write and rewrite and memorize, and then inject my performance with improvising and spontaneity, because if something feels too rehearsed, it’s not going to be fun.

BLVR: When you act on TV or in movies, much of your comedy is physical. You communicate through your expressions, your walk, your posture. So when you’re on a podcast and using only your voice, do you have to recalibrate your comedy in some way to compensate for the loss of physicality?

AD: If anything, in the podcast world, I’m relieved that I don’t have to dress like the character. [Laughs] I don’t necessarily have to do all of the physicality that conveys the character, but do as much as I need to help me feel like the character. If I do Don DiMello in a podcast, to a large extent, he’s in the room. But I’ve never done Cactus Tony outside of podcasts, so I don’t know how he walks, exactly, or how he sits. I’ve just started with the voice.

BLVR: You wrote in your Reddit AMA that in order to be a comedic performer, “you need to feel like you have something unique to share and you need to believe that whatever anyone else may think about it, it’s worth sharing.” So what is the unique thing you have to share?

AD: There’s no way to answer that without sounding super full of myself. [Laughs] But I think to a certain extent you do, at least in your own mind, have to be that full of yourself. I will take a stab at answering your question, but with the disclaimer that to talk about what animates me and keeps me going in this business might sound unappealingly egotistical.

When you’re coming up with your philosophy and approach to performing comedy, you take special note of the things you disagree with as much as the things you agree with. There’s this popular idea that’s been attributed to Del Close, but I’m not sure if that’s correct. The quote is something like, “In sketch comedy, wear your character like a hat, not a suit of armor.”

That has always bothered me, because it feels like a false choice. You ought to be able to wear your character like a Lycra bodysuit. I prefer not to wink out from behind the character as myself, saying to the audience, “It’s just me here, right, guys?” Peter Sellers is my model, and he didn’t do that—he wore his character from head to toe.

There’s a way of doing comedy that feels true to the person doing it, that doesn’t feel like clown-work or silly faces and antics, but that feels real—like you’re playing a real person who has real thoughts and feelings, and it’s very grounded. I started to watch all comedy through that prism.

When the Upright Citizens Brigade came to New York in 1996, they talked about truth in comedy, and their sketch shows seemed to have a lot of intention behind them. In particular, Ian Roberts does an amazing job of playing grounded people who are hilarious because of a particular point of view.

BLVR: You were a member of the influential UCB improv group The Swarm. Can you tell me more about that?

AD: The Swarm was constituted out of the early classes that the UCB was teaching. Andy Secunda and Michael Delaney made a short list of their favorite improvisers and asked Amy Poehler if she would direct the group. She said yes, because she had created a new improv form that she wanted to try, and so she directed us in that form, and after a while we transitioned into becoming more of a traditional Harold group.

BLVR: What did you learn from working with Amy Poehler?

AD: Commitment. If there’s one big thing you can take from Amy Poehler as a performer, it’s committing, full on.

III. THIS GUY’S A COP

BLVR: How did you come to the decision to return to Review for a limited, final run?

AD: Comedy Central came to us with the idea of wrapping up the story of Forrest MacNeil in a third and final season, and we embraced the idea. I like it when shows end intentionally, and Review, especially, has such a long form narrative that it feels like you need to give it a thoughtfully constructed finale. I don’t want to give anything away, but I’d say our basic aspiration is for Review to feel like a complete library that can be binged for a long time to come.

BLVR: You’re about to end a show that had your fingerprints all over it, as its creator, star, and one of its writers. From what I could tell, it sounds like your sole responsibility on Chunk & Bean will be as an actor. How do you feel about the transition?

AD: I really enjoy just being an actor. It’s fun to be surprised by someone else’s writing and to collaborate in creating a character and to leave all the hard decision-making to some other room full of suckers! And in this case, the script is really funny so I know I’m in good hands. That said, I probably have the most fun on projects where there’s some room to improvise, too. It’s hard for me to shut off my writer brain completely. The guys who created Chunk & Bean have been watching me improvise at the UCB for years, and I think they’ll be open to my input and impulses and tendency to, you know, not always say things exactly as they’re written.

It is also true that I loved being one of the creative driving forces behind Review, and my podcast too. It’s so satisfying to be able to say “I made that. I made so many of the decisions that made that what it is. I see myself all over this piece of work.” So, stressful as that can be, I will definitely do that again. I have a couple of ideas for shows that I would love to bring to fruition in some way at some point.

BLVR: Why did you choose Chunk & Bean as your next big project?

AD: At the start of this year, with Review headed for a wrap-up, I realized I would be available to be cast in a network pilot for the first time in five years and the idea of that excited me. To me, a guy with a family, there’s a huge appeal to the stability of a regular gig making 22 episodes a year in the city where I live. That would be sweet! Obviously, that outcome is far from guaranteed when you make a network pilot, but it could happen. So I asked my agents to send me all the scripts that were out there, and I got about three scripts into the pile when I saw a character described with the words “think Andy Daly.” That was so thrilling to me, and then I read on and really laughed at the script, too. So I called my agent and was like, “Um, I think I have a pretty good shot at getting cast in this really funny show.” And my hunch was right! The character was written with me in mind by guys who have been watching me perform for many years, so it feels completely right for me.

I think the show is very smart and subversive in a sly way. I don’t know yet how the creators want to describe it, but it kind of gives me a little bit of a Freaks and Geeksy vibe, which is a very good vibe to give in my opinion. So I’m psyched to get to work on it, and I’m amazed and terrified that I get to play Anna Gunn’s husband. She is truly amazing. I hope I can keep up!

BLVR: I recently spoke to Mike Schur about how the ratings system isn’t tenable anymore because the media landscape and the way people view TV has changed so dramatically.

AD: I think that’s true, and I would go even further than that. I think Comedy Central and probably all channels are on their way toward being apps accessible on whatever the Roku of the future is. The channel’s whole library will be there, and the show is their property in perpetuity. Any time that they want to try to capitalize on that, they can. So the more episodes you’ve made, the more you have for people to discover and rediscover later down the line. I think the calculus for networks now is to look at shows and say, is this something somebody might want to watch ten years from now? Is it binge-worthy, and it is worthy of having associated with our network for decades to come? I think Review is that.

BLVR: I have one last question: Is it true Hunter S. Thompson once kicked you out of a party?

AD: Oh yeah. That’s true.

BLVR: How did that happen?

AD: I often leave him off of my list of comedic influences, which is incorrect. I have a troubled relationship with Hunter S. Thompson, not just because he kicked me out of a bar but also because it’s become clear to me that he was not a good person. His son recently wrote a book. I’m going to read it, and it’s going to be a hard read because it sounds like he was a rotten father.

But I read everything that Thompson wrote. I stumbled on a book of his—Better than Sex, about the Clinton campaign. It was one of his worst books, but I was still mesmerized by it because I couldn’t tell which things were true and which weren’t, which is kind of the hallmark of his style. I read everything he wrote in a short period of time, and then on Halloween in 1998, he did a reading at Barnes and Noble in Union Square and signed copies of The Rum Diary. It was a bizarre event. Ed Bradley from 60 Minutes was there, and Benicio del Toro and Douglas Brinkley were making up his weird entourage, and they all read from the book. I went up and got my copies of Rum Diary and The Curse of Lono autographed and sort of geeked out, and the story should have ended there. Except I’m such a superfan that I knew where he would be going after. I had read enough references in his work about Pete’s Tavern in Gramercy Square, and it was so close to Barnes and Noble that I was like, I know he’s going there.

I went there and didn’t see him, so I was like, okay, I guess I’m wrong, but let me use the bathroom before I leave. And on the way up to the bathroom, I saw there was a private room upstairs, and of course he’s in there with his whole entourage. So I’m like, well, I’m not going to bust into a private room. That’s over. I went to the bathroom, I’m washing my hands, and this guy goes, “Hey, Andy Daly. We went to high school together. What are you doing here?” I was like, “I actually came here because I knew Hunter S. Thompson was going to be here, but…” And he goes, “My girlfriend works for his publisher, that’s why I’m here.”

BLVR: That’s crazy!

AD: Insane. At that time I was selling sitcom scripts, and he said Hunter was often willing to meet writers. He brought me in and introduced me, and the seat next to Hunter was empty so I sat down with him. Weirdly enough, we’ve already been talking about Nurse Ratched, there was a woman sitting next to him who was dressed as Nurse Ratched for Halloween.

BLVR: Were you in costume?

AD: No, I was just dressed like a regular slob. Because I was introduced as a television writer, I asked him a question about why he was credited as one of the creators of the show Nash Bridges. He very casually explained that he and Don Johnson were neighbors in Aspen, and they had talked about the idea but the original concept of the show was drastically different than what it became.

It may have been because we were talking about police, I don’t know, but in the middle of that conversation I started taking off my jacket, and he goes, “Why are you taking off your jacket?” I was like, “Oh, I’ll leave it on.” He goes, “Are you a cop?” I was like, “I’m not a cop.” And then he goes, “You are. This guy’s a cop.” I stupidly decided to kinda play along because I couldn’t tell whether it was a joke or not, so I just decided to “Yes, And…” him, so I said, “There’s nothing illegal going on here, so you don’t have anything to worry about,” and he yells, “Not with you hanging around!”

Then he throws the cigarette lighter at the back of Benicio del Toro’s head so he turns around, and Thompson says, “This guy’s a cop!” Like, really yells it. And Benicio stood up like he was going to punch me, but smiled because he knew I wasn’t a cop and to him it was all a joke. So it was getting weirder and weirder, and he was getting louder and louder, and then the guy I had run into in the bathroom put his hand on my back and was like, “It’s time to go.” So I left. I never knew. Did he actually become convinced I was a cop? Or is that something he says when he’s ready to get rid of somebody?

BLVR: That’s incredibly upsetting, because the stars had to align for you to have your moment with him—so many things had to happen to get you in the room. But then once you were there, he just lost it. It must have been like meeting one of your characters in real life.

AD: [Laughs] Exactly.