In Philip Wylie’s 1930 pulp novel Gladiator, a scientist living in a small town in Colorado develops a serum designed to reorganize the genetic structure of any living animal. Creatures injected with the serum are imbued with super speed, super strength, and are impervious to physical injury. He injects his pregnant wife with the serum, and the resulting child, Hugo, is indeed born with superhuman abilities. Told not to use them, every time he inadvertently reveals his abilities, things end in disaster. He accidentally kills a high school football player during a game, and loses his bank job after rescuing a man trapped in the vault by tearing the vault door off its hinges. Hugo becomes alienated and despondent, a complete outsider in a world where he doesn’t belong who has no idea what to do with himself. By the novel’s end, Hugo ascends to the top of a mountain in a raging storm to ask God to give him some direction, some purpose in life where his powers might be useful, only to be struck dead by a bolt of lightning.

Of the seventy books Philip Wylie published in his lifetime, Gladiator remains one of only half a dozen or so still in print today. Although it contains no tights, no capes, and no arch-villains, it’s repeatedly been cited as the primary inspiration for the Superman comics, which first premiered eight years after Gladiator’s publication. But the more interesting resemblance is what the story of Hugo’s struggle to find his place in the world has to say about the author himself.

From the late twenties through the early seventies, Wylie was ubiquitous. He wrote science fiction, mysteries, satires, and social commentary. He wrote for Hollywood, academic journals, The Saturday Evening Post, and Popular Mechanics. He wrote about free speech, UFOs, foreign policy, growing orchids, and deep sea fishing. He was a newspaper columnist and a talk show regular. He was the director of an oceanographic institute and an advisor to an early incarnation of the Atomic Energy Commission.

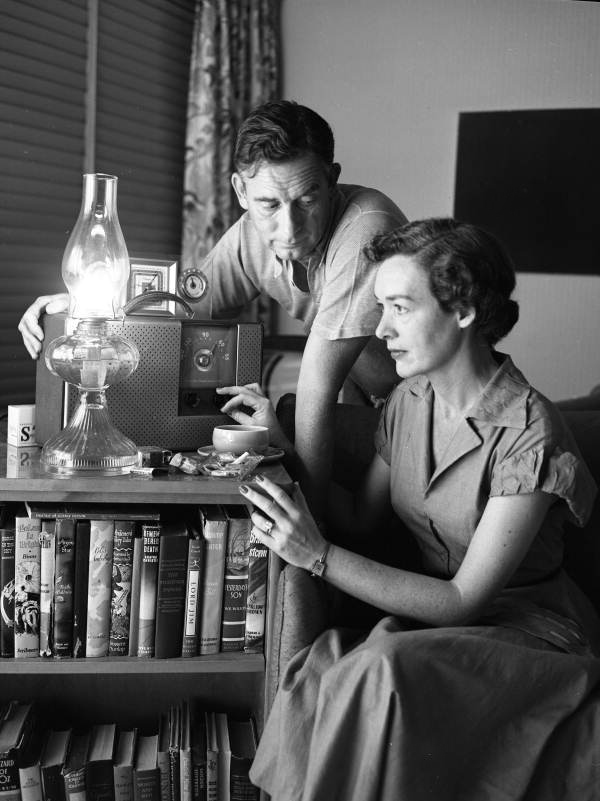

Wylie was a polymath, adept at engineering, physics, history, sociology, psychology, anthropology, and political theory, all of which he put on display in his work. He was often ten minutes ahead of his time: pushing for civil defense preparedness a decade before duck-and-cover drills and backyard fallout shelters became commonplace. He argued that women should be given equal rights in the workplace. In his 1945 short story “The Paradise Crater,” Nazi scientists use a Uranium isotope to build an atomic bomb. The story earned Wylie six months under federal house arrest, given that with The Manhattan Project still underway, no one was supposed to...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in