On Women in The Tale of Genji By Becca Rothfeld

Western literature has much to offer in the way of incorrigible womanizing. Casanova and Don Juan, names by now virtually synonymous with elaborate feats of seduction, summon up stylized images of intrigue: letters delivered by conspiratorial ladies-in-waiting, wildly beating hearts, and clandestine meetings on the grounds of Gothic manors. It is no accident that consummation rarely figures into our retellings of these narratives, which emphasize a glamorous dance of advance and retreat, pressure and resistance. The allure of the seducer is bound up with the deferral of his purported aim—with the prolonged tensions and delayed gratifications that transform his beloved’s most banal gestures into dazzling enticements. Don Juan and his ilk appeal to a fantasy of gratification without accountability. The women they seduce are always pictured on the verge of surrender, but as soon as one of them actually submits she begins to fade out of sight.

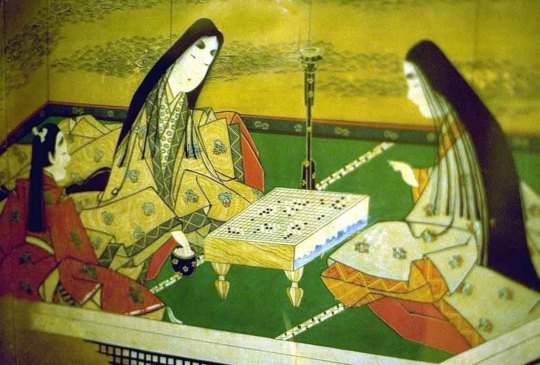

But these amorous icons, prolific as they are, can hardly compete with Genji, a legendary lover who hails from an altogether different tradition. The son of a powerful emperor, the so-called Radiant Prince skillfully navigates the landscape of a fictional Japanese court, initiating near countless trysts along the way. The most significant of his many paramours is Murasaki, whom he raises as a daughter and weds (read: deflowers) when she is still prepubescent. Genji’s insensitivity to the women he compromises rivals Don Juan’s—but his exploits were dreamt up by a woman, an eleventh-century Japanese courtier nicknamed Murasaki Shikibu, after her best loved character (her real name is unknown). It is perhaps for this reason that the liaisons in The Tale of Genji do not end at the moment of female capitulation. Instead, they continue, often disastrously, for months or years, muddied along the way by entanglements and recriminations. The book—if never the Japanese aristocracy itself—holds callous male lovers at least implicitly accountable.

Written at the turn of the eleventh century, The Tale of Genji is arguably the world’s first novel. Though it appeared long before Western literary scholars had the familiar concept of a “novel” at their disposal, it spans over a thousand pages and is undeniably novelistic in scope. The work purports to take place during the reign of a fictive emperor, but the milieu it depicts closely resembles the one in which Lady Murasaki lived and worked. During the Heian period (794-1185), male nobles and royals were bigamous: they had multiple “consorts,” each of whom presided over a separate court. This arrangement fostered competition between wives, who were forced to jockey for their husband’s time and affection. Consorts found themselves at pains not only to forge...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in