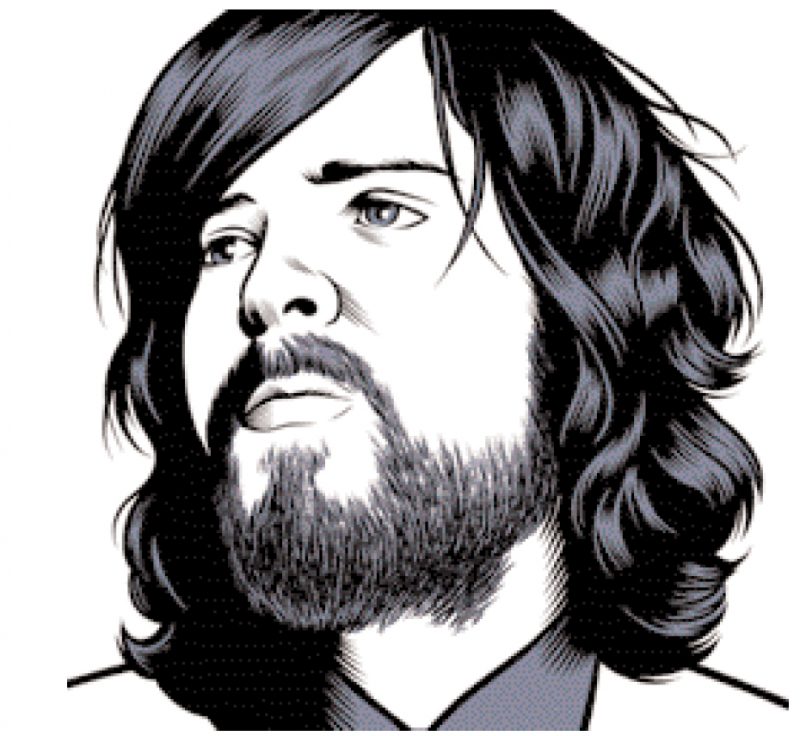

Devendra Banhart, whose name was given to him by an Indian guru his parents followed (“nothing cultish,” he says), was born in Texas in 1981, but spent most of his childhood in Caracas, Venezuela. He later moved to Southern California, where he petitioned unsuccessfully for a skate park to be built near his home. After high school he enrolled in the San Francisco Art Institute, dropped out a couple of years later, and started recording songs on a 4-track lent to him by a friend.

What he came up with was a cobbled mix of acoustic guitar, singing, mumbling, clapping, stomping, and hissing tape. Some songs came to him so spontaneously that they had to be retrieved from friends’ answering machines. The ultimate result was the rambling and beautiful Oh Me Oh My… The Way the Day Goes By the Sun Is Setting Dogs Are Dreaming Lovesongs of the Christmas Spirit, released in 2002. He has since put aside the solo stuff and started playing with a full band, the Queens of Sheeba, with whom he’s been making music he calls “space reggae.”

Banhart is a gifted and prolific songwriter (he released two full-length albums last year, Rejoicing in the Hands and Niño Rojo, despite an uninterrupted two-and-a-half year tour) who plays in a range of styles, having drawn comparisons to Bob Dylan, Syd Barrett, William Blake, Tiny Tim, Marc Bolan, Beck, and Billie Holiday. Listening to his records or seeing him perform live, it’s easy to feel like Banhart is channeling just about every musical genre imaginable. But what he’d really like you to pay attention to are the stories in his songs.

His latest album, Cripple Crow, was released in September.

—John O’Connor

I. SAMMY HAGAR’S SUSHI

THE BELIEVER:You’ve been on the road for a couple of years now.What’s that been like?

DEVENDRA BANHART: Well, I toured with no break for two and a half years, and toward the end I was like a junkie looking for a vein in his dick.That’s a horrible, sad, depressing metaphor, but that’s the way I felt. I really burned out. I lost the sense of where home is. Then I realized that home is anywhere I am, and I made it all right to tour like that. But in the end it wasn’t healthy. I couldn’t write anything.

BLVR: Did it affect your playing?

DB: No,but I did just want to get through it. It’s funny— I’ve just now been thinking about some of the reactions of people on this tour. Every night someone would yell, “Your band sucks!” I’ve never had to deal with that before. I mean, I’ve had to deal...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in