The opening was dazzling. The middle was dazzling. The ending was dazzling. It was like a steeplechase composed entirely of hurdles.”

The opening sentences of Renata Adler’s second novel, Pitch Dark, could almost be taken to describe her first. Speedboat is dazzling—in the sense, among others, that it’s disorienting, opaque—and if it’s “like” anything at all, a steeplechase of hurdles could be it. Then again, it might not be. You could say Speedboat is like a party line, like a still-wet painting stared at from too close, like an overheard conversation dominated by twenty-six people, like a radio with a restless operator twiddling the dial, like a game of chess (its first chapter is called Castling, and there’s something of the rook’s lateral and protective motion to how it unfolds): but, insofar as it resists most of fiction’s conventional organizing principles, the novel is a problem unto itself.

The book’s gnomic, jagged, centrifugal style is incredibly hard to account for, and to describe. Adler’s book has been championed—by David Shields and David Foster Wallace, among others—as a kind of anti-novel, a collage, or an assemblage: it’s said to have no plot to speak of, and while this description is almost true (there’s the ghost of a narrative, at least, a dramatic dilemma that surfaces and recedes over the course of 178 pages), it doesn’t really get us any closer to understanding what Speedboat is. It defines the novel in terms of what it lacks, which is always a bit of a dodge, and a disservice.

So Speedboat is an anti-novel, which is to say, an atypical novel. But the book isn’t particularly interesting just for failing to deliver the standard-issue dramatic goods, a failure it shares with hundreds of other experimental fictions of its era. (As Adler herself put it in her review of Godard’s Weekend, “There are few things more disgusting aesthetically than an audience avant garde on principle.”) Despite its title, there isn’t really much propulsive motion in Speedboat at all (the narrator, a reporter named Jen Fain, writes alternately for a tabloid and in a more investigative context; eventually she gets pregnant), yet somehow this doesn’t render it static: line for line and sentence for sentence, it seems to me thrilling.

All the men in the room had drinks in both hands. They had tried to extricate themselves from conversations by saying, “I guess I’ll have another drink. May I get one for you?” The trouble with this method is that it takes people right back where they came from; it is impossible to approach with one lady’s gin and tonic another lady who may be drinking Scotch. Escape procedures, however, were in full force. Some people, in a frenzy of antipathy and boredom, were drinking themselves into extreme approximations of longing to be together. Exchanging phone numbers, demanding to have lunch, proposing to share an apartment—the escalations of fellowship had the air of a terminal auction, a fierce adult version of slapjack, a bill-payer loan from a finance company, an attempt to buy with one grand convivial debt, to be paid in future, an exit from each other’s company at that very instant.

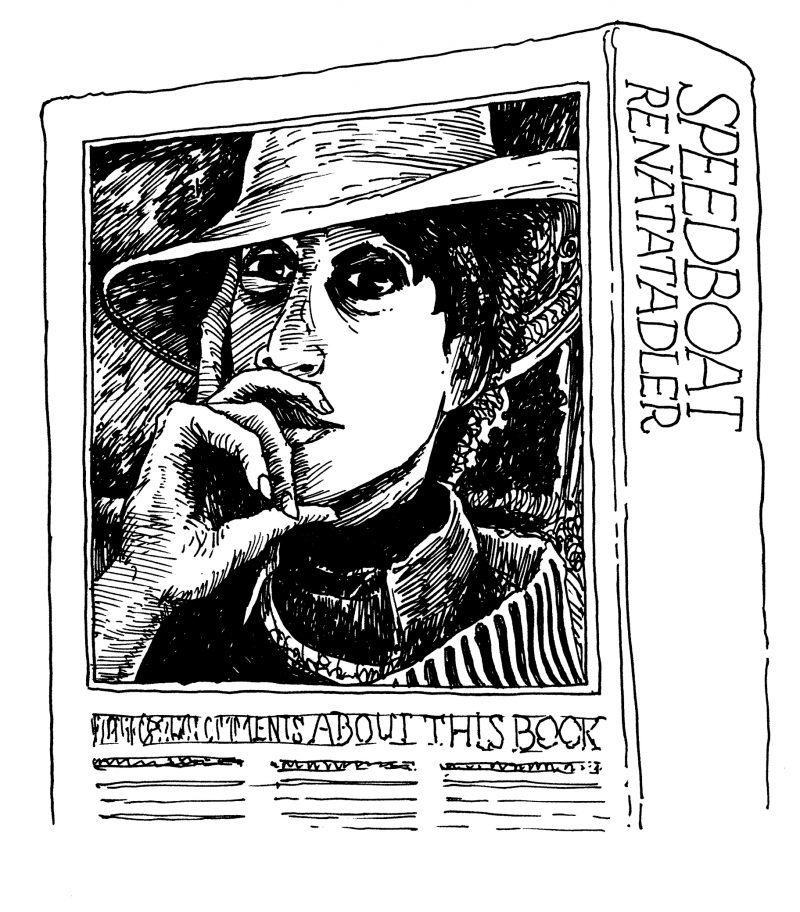

This passage is typical of Adler—it’s observant, funny, urbane—but, in context, it doesn’t particularly stand out. I plucked it from Speedboat practically at random, and even so it shows a goodly portion of what Adler gets up to. And, perhaps, what the author herself got up to in real life. In Adler’s author photo, taken by Richard Avedon, she wears the look of someone familiar with parties, probably important ones. Her tanned and liquid-eyed face is half-obscured by her own hand and an enormous hat, her affect that of a celebrity seeking anonymity on a yacht off the coast of Capri. A 1983 New York magazine profile of Adler is littered with boldfaced names—Jacqueline Onassis, Avedon, and Brooke Astor are listed among her friends.

For certain, Adler ran with a fast crowd. After graduating from Bryn Mawr and studying comparative literature and philosophy, briefly, at Harvard, Adler was hired in 1962 to write book reviews at the New Yorker (anecdotally, at least, she toppled into the position despite not being a regular reader of the magazine), where she remained on staff for decades, albeit ambivalently. In 2000, she would publish a prosecutional tell-all called Gone: The Last Days of The New Yorker.

Apparently feeling book reviewing was “not quite honorable” as a primary means of support, she took up writing investigative pieces, and then, in 1968, again in a way that’s related as strikingly accidental—she had run into the editor Arthur Gelb at a party, and he hired her on the spot to replace film critic Bosley Crowther, even though she had only ever reviewed five movies—she took over a daily movie-review column at the New York Times. This, apparently, was uncomfortable, too. Adler referred to the whole ordeal as “the peculiar experience it always is to write in one’s own name something that is never exactly what one would have wanted to say.” (This, of course, might describe writing anything, but Adler’s ambivalence reared its head early on, a tortured apprehension that seemed to watermark her thought in all its forms.) The relatively corseted A Year in the Dark: Journal of a Film Critic, 1962–69 (1969), a compilation of Adler’s New York Times film reviews, and Toward a Radical Middle: Fourteen Pieces of Reporting and Criticism (1969), a selection of pieces she wrote for the New Yorker between 1962 and 1968, contrast sharply with the ferocious Canaries in the Mineshaft: Essays on Politics and Media (2001), a collection of nonfiction pieces written, for the most part, during and after the mid-1970s, when her career as a novelist was under way. (Not that fiction cured her ambivalence, either: by the time Speedboat was published, Adler had enrolled at Yale Law School.)

Speedboat evolved out of a set of short stories she published in the New Yorker. She reflected on the decision to write it thus: “I can’t be saying this, but in a way I think that if you’re going to write, after a point some of it better be fiction.” Both the amount of hedging in that sentence and the involuted threat with which it concludes speak volumes.

The book is a whorl of parties and apartments, but like Paula Fox and, to a lesser extent, Joan Didion (the two writers who most persistently assert themselves to me as Adler’s “peers,” along with the Don DeLillo of, say, Players and Running Dog), there’s a burlesqued violence that relentlessly crests the surface. The setting—a cocktail party, the most Manhattanite imaginable—is Woody Allen’s, and yet the method is Paul Schrader’s: “frenzy” is never far from the surface. In 1976, the year the book was published, Adler also produced a scathing article for the Atlantic, in which she argued that Watergate was a soft cover-up for a far more horrifying scandal, suggesting that Nixon may have received campaign contributions from the South Vietnamese in exchange for keeping troops there longer. And so, at its heart, Adler’s book isn’t a mere urban valentine, even a dystopic one: even at its most New York–centric, the book isn’t really “about” the city itself. What it is is a war novel.

Here, for example, is the book’s epigraph, taken from Evelyn Waugh’s Vile Bodies:

“What war?” said the Prime Minister sharply. “No one said anything to me about a war.

I really think I should’ve been told…”And presently, like a circling typhoon, the sounds of battle began to return.

But what’s in an epigraph? And couldn’t Speedboat as a whole be read as a steeplechase composed entirely of epigraphs? The book’s parts, though, seem to bear the same relationship to one another that an epigraph does to a text: they comment, and shed a kind of elliptical light, but they fail to establish a sequential relation from one paragraph/scenelet/sentence to the next. So what’s to say that Waugh epigraph is more than a red herring? Besides its echo in one of the book’s seven section titles (What War), that is?

Everything. Speedboat’s seemingly breezy opening lines (“Nobody died that year. Nobody prospered. There were no births or marriages”) are, of course, impossible: they inaugurate the novel’s dreamy weirdness while at the same time establishing something reportorial in its mission. Am I alone in hearing a distant chime of Hemingway’s “In Another Country” here? (“In the fall the war was always there, but we did not go to it anymore.”) The scale is global, even as it narrows in that very paragraph (“The city, of course, can wreck it…So many rhythms collide”) to define a more specific territory. And, once having contracted, it expands again: to the Mediterranean, to Egypt. At times Adler sounds like Joan Didion overloaded with sensation and quickened, or just fried, by wit:

I stole a washcloth once from a motel in Angkor Wat. The bellboy was incensed… To promote the general welfare and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity—I believe all that. I go to parties almost whenever I am asked. I think a high tone of moral indignation, used too often, is an ugly thing.

I get up at eight. Quite often now I have a drink before eleven. In some ways, I have overshot my mark in life in spades.

The question of the book’s structure gets its most direct address near the end, when the narrator simply reflects, “There are only so many plots. There are insights, prose flights, rhythms, felicities. But only so many plots… I had begun to believe that a story line was a conceit like any other. One has only to take to bed, though, with a Seconal and a thriller, racing toward their confrontation, for it to become clear that this is not quite the case.” Yet too many appreciations of Speedboat stop there, with the dismissal of plot as a “conceit,” when in fact Adler dismisses no such thing. The passage continues:

Maybe there are stories… like solitaire or canasta; they are shuffled and dealt, then they do or they do not come out. Or the deck falls on the floor. Or a piece of country music, a quartet, a parade, the flag—all the things one ought by now to be too old for—touch, whatever it is.

A parade, the flag: almost but not quite casually, the book brushes up against emblems that are not quite those of peacetime. It also suggests that, for all its fragmentation, Speedboat is—after all—a narrative like any other. It will or it won’t “come out.” The way it eventually does, in a chaos of spies and hostages, is satisfying, even if it isn’t optimistic. Adler’s view of human, romantic interaction ain’t rosy, but the prose itself is relentlessly spry:

In any group of two or more, it seems, somebody is on trial…Under the law, a person can be said to plan alone or to plot alone, but not to conspire alone. There are other things, of course, no one can do alone: be a mob, or a choir, or a regiment. Or elope.

Here, Kafka elides into Jane Austen, as that final romantic fragment sets the aggression and paranoia of the foregoing on its ear; but it’s worth pointing out, too, that Adler, like Austen, is something of a moralist. There’s a gorgeous riff, for instance, in Pitch Dark, about a particular absurdity that inheres in the American justice system: “a legal job no sooner comes into existence than it generates, immediately and of necessity, a job for a competitor. I can think of no other line of work where this is true.” And in that same book—whose fractured plot is mainly driven by an imaginary, not-quite-existent crime the narrator believes herself to have committed—she writes:

What’s new. What else. [These] may be the first questions of the story, of the morning, of consciousness…What’s happened here, says the inspector, or the family man looking at the rubble of his house. What’s it to you, says the street tough or the bystander. What’s it worth to you, says the paid informer or the extortionist… And the sentient man, the sentient person says in his heart, from time to time, What have I done.

That question of culpability, of responsibility as it relates to all human endeavor, is all over Adler: it’s in her work as a media critic, as a movie reviewer, as an investigative journalist, but it’s most interesting, I think, in the novels. Perhaps because there it’s the most conflicted, the most tattered. Perhaps, too, because she apparently had such difficulty with them. The New York magazine article quotes her thus on her routine: “I wake up at five or six. I have breakfast. I think, ‘I should be writing.’ And then I think, ‘Well, maybe after a little nap.’ And that way several years pass. Truly, several years pass.”

Both Speedboat and Pitch Dark are set to be reprinted by NYRB Classics in March 2013, but the reason these books, and Adler’s whole body of work, really, should be more widely available isn’t because they’re fascinating or mandarin or even because (though of course it’s true) they’re products of a late-twentieth-century brilliance on a par with, say, Thomas Bernhard’s. The real reason is because her work hasn’t dated: its depth of engagement on every level—with private life and the life of state—its comedy and perspective, its shrewd observation of everything from literature to politics to manners and back again, these qualities mark Adler’s work as fathomless, as damn near inexhaustible.

Of course, the question then is why is there so little of it? One suspects Adler herself isn’t immune to the scouring power of her own eye; it might be all but impossible to sustain that level of observancy and the flexion necessary to invent things. But to whatever extent both novels remain such vital enigmas, reading Adler’s collections of investigative and cultural criticism published before and after sheds some light. Adler’s fictions are models of proportion, not least for the way they lay out private crises and political moods (neither is really a “backdrop” for the other, which is part of what’s confusing about them as “novels”), but also in their mastery of a tone in which sympathy never overwhelms irony, and vice versa. The early nonfiction collections, by contrast, are a little stiff in spots. Watching Adler stalk the Sunset Strip in a 1967 New Yorker piece called “Fly Trans-Love Airways” (reprinted in Toward a Radical Middle) is disheartening; one yearns for a more nimble, Didion-like closeness to the teenagers floating around a Fairfax Avenue coffee shop called the Blue Grotto and to the band she mistakenly tags with a definite article: “the Love.”

At the same time, Toward a Radical Middle encodes material that would play out in her subsequent fiction, and provides us with the closest thing we have to an Adler manifesto. Its introduction draws a sharp line between “true radicalism as opposed to what I would call the mere mentality of the apocalypse,” insisting against overheated rhetorics and popular binaries in favor of… what, exactly? Not “moderation,” although Adler flashes what some might consider a conservative streak as she suggests that “what has muddled terms” and given rise to the “radicalism of rhetoric, theater, mannerism, psychodrama, air” is the disappearance of “the Just War as a romantic possibility.” It’s rather more what the title implies, a “radical middle” (Adler insists in a 2004 interview with Robert Birnbaum that the title was a joke, a provisional name with which the book inadvertently got saddled, but that doesn’t make it less suggestive): a possible contradiction, in other words. It’s nothing she can resolve—who could?—but it’s the tension that gives all her books their living depth.

Adler’s later criticism is far more strident, but that doesn’t mean they’re less acute: her legendary evisceration of Pauline Kael’s When the Lights Go Down (7,900 words in which an assessment of Kael’s book as “line by line, and without interruption, worthless” serves as a jumping-off point rather than a conclusion) might be cruel, but it’s also persuasive. The same can be said of “A Court of No Appeal,” the steely piece in which she defends herself against a compound set of attacks (nine, by Adler’s count: a series of reviews, letters, op-ed pieces, and features) from the New York Times alleging that she had defamed Judge John J. Sirica in her memoir, Gone. One gets the sense Adler’s diminished visibility these days stems directly from these attacks. One gets the sense, too, that she launched these fights not just deliberately but with an anticipation—even a hope—that there would be blowback. Adler’s pummeling of Kael’s book came just a year and a half after she had, in fact, filled Kael’s role as the New Yorker’s film critic for six weeks, in the fall of 1978. Perhaps it’s easier to manage one’s quarrels with others than it is to handle the ongoing argument with oneself. It is certainly less exhausting. But tilt at enough powerful windmills—there’s also Reckless Disregard: Westmoreland v. CBS et. al., Sharon v. Time (1986), in which Adler hammers CBS and Time magazine, and Irreparable Harm: The U.S. Supreme Court and the Decision That Made George W. Bush President (2004)—and you’re bound to be marginalized.

And yet every one of these books seems to belong, still, to the center. It’s a joy to see such intelligence turned on topics like soap operas and Sesame Street (she describes Ernie as “neurotic, easily moved to tears” and refers to “amiable, senile Muppet pedant, Herbert Birdsfoot”), alongside definitive essays on Kent State and the Starr Report. Adler’s intelligence never fails her: she can be watching the most, or the least, corrupt proceedings and retain an equal skepticism. It’s humor that provides our delight: not the neurasthenic, and calisthenic, self-questioning of a Didion or the lethal ethical observancy of a Paula Fox, though I’d reckon Adler exceeds them each on either score. It’s wit, and temper, both words I use in their most far-reaching definitions: a sense of existence and behavior that’s practically Greek in its feeling for fairness, its efforts to align the most radical tensions.

It isn’t Greek, though: it’s American. And Adler’s books, those books I remember first spying on my parents’ shelves as Watergate-era totems (Speedboat up there, surely, alongside Cheever’s red collected stories and Judy Blume’s Wifey), are as American as anything, as much so as Whitman or Dickinson. Like theirs, Adler’s feel for the intimate dilemma—the over- or underflow of the self—takes on a grand, totemic dimension, enough so that distinctions between the “personal” and “political” seem moot. There’s no bottom to these novels, and no end. To wonder why there are only two of them, to speculate upon Adler’s current doings (in her interview with Birnbaum, the most recent I could find, Adler claims not to have given up fiction at all, describing it as “all I want to do”), to scrutinize—ahem—a handful of remarks on ratemyprofessors.com that are by now a few years old (“Today she told us that a scene from Woody Allen’s “Manhatten” [sic] is taken from a conversation she had with Woody. That’s crazy!” wrote one BU student in 2005), all this is kicky but in fact irrelevant. The books themselves must be brought back to the center, where true radicalism, and real exceptionalism, always belongs.