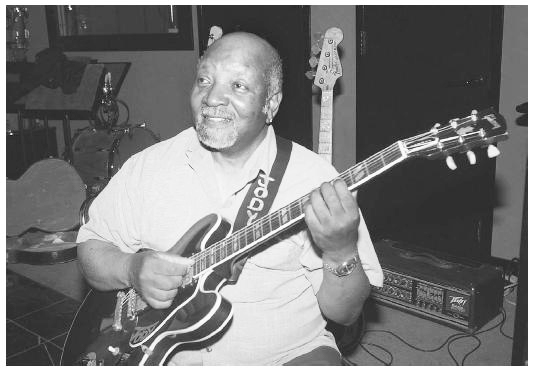

This is the first oral history in our “Pause” series, which features artists, musicians, filmmakers, writers, and athletes who took a significant break in their careers to do something else before returning to their artistic careers.

JODY WILLIAMS: Harmonica was my first instrument, not guitar. I was doing a talent show in Chicago, and Bo Diddley was on the show playing the guitar. I watched him, and that was the very first time I had ever paid any attention to the sound of the guitar. I liked it. So we did this show, and when we got backstage we played a little bit together. I asked him, “If I got my mother to get me a guitar, could you teach me a tune or two?” The next week I spied a guitar in the pawn shop, and my mother bought it for me. It was $32.50, an old Silvertone with a black pickup on it. So Bo taught me how to run a bass line behind him while he sang and played, and that’s how we got started.

But I wanted to learn something other than just what Bo Diddley was playing, so I went to two guitar teachers. I told them, “I want to learn how to play some music, right now.” But they wanted to waste your time and money teaching you to play only the scales. Neither one of them could teach me what I wanted to learn, so I just started going to the nightclubs, hanging around and learning from people like Muddy Waters. I was only seventeen years old when I left home, and I wasn’t supposed to be in the clubs until I was twenty-one. The police came in there and started looking around, and I definitely looked young, because they would come up and question me, “How old are you, boy?” I got my voice down as low as I could and said, “I’m twenty-one,” and I turned my guitar and kept playing. So I was twenty-one years old for four years.

Naturally, I learned more, did some traveling on the road. Little by little I started doing some recording behind people. I became a studio musician for Chess Records, and I participated in a lot of things on the Checker and Argo labels. I started playing with Howlin’ Wolf in 1954; we were introduced in the office of Leonard Chess.

In ’58, I went into the service. I spent a year and a half in Germany, stationed in Dachau. I even played music onboard the ship to entertain the troops on the North Atlantic.

Before I left for the army, I had written one of the biggest hits in the country with the help of Bo Diddley, and it was stolen from me. You ever hear that song “Love Is Strange” that Mickey and Sylvia did? I wrote that. I remember playing “Love Is Strange” onstage one time, and seeing some movement behind the curtain. I look back there and I see Mickey Baker, stealing all he can get. Bo ended up letting Mickey and Sylvia have that song, and they gave him two thousand dollars. To this day, I haven’t seen a dime of that money.

Arc Music eventually filed a lawsuit against the firm who released that recording. When I finally testified, I think Sylvia was in the courtroom. There were music detectives in there with stereo equipment set up. They asked me some questions on the stand, and then I went back into a room behind the judge where I couldn’t hear anything. The case was left unsettled, and I ended up going back to Chicago. About a month later, I heard we had lost the case. I didn’t get anything, even though there’s a hell of a lot of money mixed up in that song.

It was around that time that I decided to give up on everything. Music had left a bad taste in my mouth. I just changed my outlook on life, period. I played for a little longer, but I finally decided to put my guitar under the bed. I didn’t plan on playing again, ever. I was just disenchanted with the whole thing. It brought back painful thoughts. I decided to put my guitar under the bed and go to school.

I went to school for electronics; I learned about AM/FM radio, black and white and color television, air conditioning, refrigeration, appliances—I studied all of that. I took a job as a technician at Embassy Radio. But I wasn’t making the money I thought I should have been making, so I went to another night school downtown to study computers. I went on the GI Bill. I learned how to work all the IBM control boards, and I punched data for the IBM 360 computer. After that, I applied for a job at Xerox Corporation, took some tests, and got a call from them the next week saying they wanted me to start. I called my workbench boss at Embassy, and I looked at my watch and told him, “It’s a little after one-thirty now. When four o’clock comes, I want you to be here with a check. I want every goddamn dime I got coming. You put it in my hand, and I will be out of here. I got a much better job.” And he did; he hurried up to the office to tell them what I’d said. They tried to convince me to stay, but I said, “I got a better job, a career, a suit and tie and all that stuff, and I’m looking forward to it.” So they gave me the money, and I left there that day. I was a Xerox technical engineer for twenty-six years.

After I retired from Xerox Corporation, in ’94, I saw an advertisement: this ATM company was looking for technicians. I was curious as to how the inside of those machines operated; I had never seen the electronic circuitry. So I applied for one of the jobs, and I got it. I came back to Chicago, where I’d been living since I was five years old, and for sixteen years I was an ATM technician. I had a uniform, wore a bulletproof vest, big magnum on my hip. I retired from that job in June 2011.

While I was working, the wife would sometimes tell me that if I decided to play guitar again, I might get a better outlook on life. I thought about it, but whenever it would cross my mind, I’d go out and do something else. I’d maybe get one of my guns and do a little shooting. One day an acquaintance of mine came to my house and asked me if I wanted to see Robert Lockwood Jr. play that night down at Legends. So I told him I’d go down there with him on one condition: “As long as nobody knows who I am. Because once they find out who I am, they’re gonna throw a guitar in my hands.” So he agreed to it, and we went. While he was playing, Robert Jr. looked over and saw me, and right away he knew who I was. He hadn’t seen me since I played. We talked afterward, and when I got home I started listening to some old tapes that my drummer had made when the band was playing various clubs. It had been so long since I’d heard those tapes. The whole thirty years that my guitar was under the bed, I did not listen to any blues. I was away from all that stuff. My wife had me listen to light jazz. So when I heard the tapes, I said to myself, That sounds pretty good. And listening brought tears to my eyes, it really did. I started feeling sorry, saying I shouldn’t have abandoned my guitar. I felt bad about it because I didn’t know we’d sounded that good. That’s when I started practicing my guitar again.

Soon there was a guy who called me and asked me to be on one of the shows that he was having in Chicago. But I said no; I wasn’t going to get on anybody’s stage sounding like a rank amateur. I was rusty and I wanted people to remember me the way I was. So I went on practicing my guitar, but when it started getting close to that date, I had a change of heart. I called and told him I would like to be on the show. He said that all the money allotted for the show he had promised to the other performers, but I told him, “You don’t have to pay me. I’ll do it for nothing. I just want to see if I can run with the big dogs again.” So I played that night, and it made me feel good. A lot of people remembered the name and enjoyed my playing. From there, one thing led to another. I started getting engagements, doing a couple club dates in Chicago. And then a record executive from Evidence Records came to my house, and I ended up recording two albums.

I’m at a point in my life now where I don’t have any restrictions, since I’m retired. A whole lot of things have passed now. If anybody wants me to go to Japan or Europe, I’ll go, play my guitar, make me a little money, come back home. I do enjoy it. Thirty years is a long time to go without playing. When I put my guitar under the bed, I said to myself, Hell with music. I was listening to public radio one day not so long ago, and I heard Mickey Baker being interviewed. I turned the radio off.