An Interview with Perec Scholar and Translator David Bellos

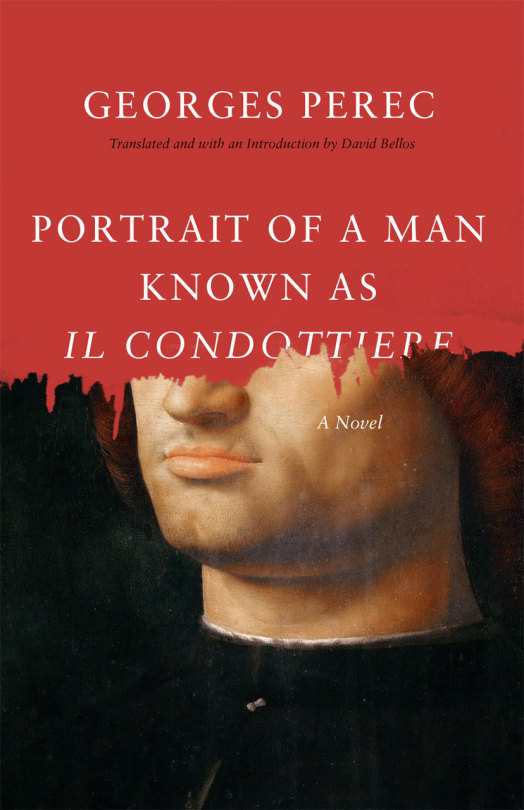

Georges Perec’s most revered tomes, palindromes, lipograms and dérives will always share an association with the French author’s membership in the Oulipo (Ouvroir de littérature potentielle or “workshop of potential literature”) beginning in the mid-1960s. But the recent publication of Perec’s first, “lost” novel, Portrait of a Man Known as Il Condottiere some fifty-five years after its completion, reveals a precocious, but protean, aspect to his work. The then-impecunious Latin Quarter office worker and discharged paratrooper—whom French scholar and perennial, Perec translator David Bellos refers to as “Perec before Perec”—was contracted in 1959 by Gallimard to complete the one hundred and fifty page manuscript under the working title Gaspard pas mort.

With nearly three years of writing, rewriting and revisions invested in the text, Perec ultimately abandoned Il Condottiere when the publisher refused to continue with the project. As the popular fable of Perec goes, the suddenly celebrated author of Things: A Story of the Sixties accidentally disposed of all copies of Il Condottiere and numerous correspondences some years later when success allowed him to move apartments. While a brief reference in his autobiographical W, or Memories of Childhood notated its provenance, Perec’s unexpected death in 1982 appeared to ensure its complete disappearance.

The plot of Il Condottiere follows ambitious protagonist Gaspard Winckler’s failed attempt to counterfeit the titular portrait of a medieval warlord by 15th century Italian painter Antonello de Messina to murderous consequences. The horrible act itself, occurring just out of frame of the narrative, forces Winckler to parse the complex motivations (or lack thereof) that preceded his crime. This vaguely Camusian tale of death and forgery, with a soupcon of Poe-inspired psychotopology (Winckler is locked in a basement for more than half of the text), finds Perec dabbling in a turgid, modernist narrative of the alienated artist unchained by an inexplicable act of violence. As Bellos writes in the book’s introduction, with a narrative absorbed in the bipolarity of authenticity and the counterfeit, Winckler’s desire “to achieve the impossible feat of creating a real masterpiece that will be recognised (and therefore purchased) as a genuine Antonello… produces an authentic image of his own true self—an evasive, indeterminate fraud of no fixed identity.” The voluble self-interrogation dominating the majority of the narrative proceeds along a narrow thread that stitches together the false artist and the true criminal.

Through Bellos’ exhaustive research—his translation of Life: A User’s Manual and colossal biography Georges Perec: A Life in Words effectively introduced Perec to English speakers—carbon copies of Il Condottiere were unearthed beginning in the 1980s and finally published by Editions du Seuil in 2012. On the occasion of the University of Chicago’s new publication of the Bellos translation, I asked the distinguished French literature scholar and Perec expert to expound on the legend of the Condottiere. As part of our conversation, he and I discuss the different challenges in Perec’s early career, the question of preserving juvenilia, and the roles of detective and deceiver that comprise a literary cosmology of the Oulipo master.

—Erik Morse

I. I PROTEST!

THE BELIEVER: In the introduction to Il Condottierre, you write of the long investigation you undertook to locate a copy the novel. How much of a detective’s identity do you think a literary biographer must assume in the exposition of his subject?

DAVID BELLOS: I’m not a detective, I’m not looking to solve any crime, and I don’t think my French critics mean only to be admiring when they call me “Sherlock Holmes” (in four syllables). Finding lost works is a serendipitous side effect of careful reading, attentive listening, and knowing how to spell names properly so you can look them up in the telephone directory.

BLVR: I suspect this is precisely the kind of literary mystery that Perec himself would have appreciated as a detective novel enthusiast and lover of puzzles. Did you have any sense as Perec’s first biographer that the author himself had perhaps anticipated the scrutiny of his extant manuscripts.

DB: Not in the early stages, for sure. However, after he won the Medicis Prize for Life A User’s Manual in 1978, a few fans and hobbyists started to take an interest in his work—collecting ephemera and bibliographic rarities, or coming to ask him about the rules and constraints he used. At that point I think he began to take on board the fact that his personal archive had some importance and value. But he did not do much about it. He had no reason not to believe he would live many years more. But here’s a puzzle of a different kind: in 1975, he gave away, for sale at a charity event, the manuscript of W or The Memory of Childhood. Was that because he knew it would be a key to solving the puzzle of Georges Perec? Or because he really didn’t care to hang on to it? At any rate, it has ended up in the Royal Library of Sweden, a country Perec never visited once.

BLVR: Since Condottierre is so different from everything else in Perec’s oeuvre, is it tempting for the reader to relegate the novel to a young writer’s literary misadventure?

DB: Condottiere is distinct from Perec’s other juvenilia. It is the first work that he sought to publish, and the only one that Gallimard ever took an interest in. The decision to release it (but not to allow publication of several other early and less finished pieces) makes sense to me.

BLVR: As a translator, biographer and archivist, what kind of obligation do you believe we have in publishing unfinished and “lost” texts posthumously?

DB: “We” don’t have to take such decisions—unless “we” happen to be the owners or managers of the literary estate. I put the matter in the passive form out of respect for the feelings of the person who does have to make that call.

BLVR: How out of step with the contemporary literature of the day would the book have been had it been published at the end of the 50s?

DB: Well, you can’t replay the tape to find out, but my own guess is that it would have fallen flat on its face. It resists political appropriation, and in the hyper-politicized world of French literature of that time no faction would have any interest in promoting it. The cleverness of [his follow-up novel] Things, which is at bottom not a political novel at all, is to permit or even prompt appropriation by the anti-capitalist, anti-American, anti-modernizing strands of both left and right.

BLVR: With the fashionability of existentialism in the 40s and 50s, what do you think was the general, literary consensus toward the pre-war Surrealists, the Symbolists or the Decadents, whose works collectively bear a major influence on Perec?

DB: I’m not sure I even agree with your premise! Symbolist and decadent poets weren’t as far as I know “major influences” on Perec, and his wonderful short story, A Winter Journey, which shows fair knowledge of the field, could be considered quite aggressive toward them. In the post-war period, surrealism carried on, of course, but it provided pretty much the counter-model for Oulipo.

BLVR: I suppose I mean less the “codified” Surrealists and more the pataphysical wordsmiths like Raymond Roussel, Jean-Pierre Brisset or Alfred Jarry whose experiments with palindromes, puns, and other rhetorical devices seem indebted to the Surrealist frame of reference.

DB: Several of [Oulipo’s] founding members—Queneau, Arnaud, Latis—had been close to Surrealism in the 1930s, and had an abiding interest in “literary lunatics” like Roussel and Brisset. But as the group expanded from around 1966 with the co-option of younger writers like Roubaud, Perec and Benabou, pataphysics came to be seen as something almost antique, an adolescent aberration of the old guys in the group. But the Perec of the Condottiere—Perec before Perec, so to speak—hadn’t yet come across Queneau or any of the other members of his group, and to judge by his correspondence and the small amount of reviewing that he did, his interests were not at all of that kind. Young Perec read Flaubert, Verne, Ivo Andrić, Thomas Mann and Robert Antelme, not Breton, Soupault or Raymond Roussel.

BLVR: In your biography, you write that Perec did seek out the opinion of Simone de Beauvoir on Condottiere. Is there any record of her response?

DB: The connection with Simone de Beauvoir was through Perec’s cousin Bianca. I remember her telling me that Simone thought the young man should do anything in life except write, but I don’t recall if that was ever written down. The same advice was given to Balzac by a distinguished family connection at the same age.

BLVR: Perhaps I’m wrong, but it often appears that American and Anglo readers group Perec in this very obscure niche of avant-garde or recondite literature, which similarly experimental writers like Borges, Cortázar, Nabokov, Burroughs and Pynchon have largely avoided. Do you think this purely a translation issue or is he just more difficult to read?

DB: Not at all! Perec is not in what you call the “obscure niche” of the avant-garde! He’s read by lots of people, and gets quoted in the most unlikely places in the English-speaking world. Life A User’s Manual goes on selling around 2,000 copies a year worldwide in English translation, which, after twenty-five years in print, makes Perec one of the most read “foreign modern classics” in the Anglophone world. He loved Borges and Nabokov, of course, and there are quite a few bits of both in Life A User’s Manual. And no, Perec is NOT more difficult to read than Burroughs or Pynchon! On the contrary! I protest! But maybe that’s because I am (a) the translator and (b) European.

II. MARKET RESEARCHERS WITH DATA-SORTING SKILLS

BLVR: What did you uncover about Perec’s fledgling writing career in the 50s prior to his membership in the Oulipo—“Perec before Perec”—that might have marked the transition between his early writings and mature works?

DB: There are many formal conceits and thematic topics that are common to the earliest and latest works—split narration, indeterminate perspective, word play, forgery and deception, revenge. I don’t see any “transitions” as such, just a constant search for adequate tools through which to pursue the same broad literary and personal objectives.

BLVR: So was there any major artistic significance to Perec’s move to Tunisia with his wife Paulette between the writing of Condottiere and Things?

DB: None. She had a job and he had none, simple as that. In addition, his old philosophy teacher from school was now a professor at the University of Tunis and his old classmates from secondary school in Étampes were now close to running the country. It was something of a cop-out from a Latin Quarter life that wasn’t going anywhere, but also a hope that he would have time to write. But as you know from Things—or from my book—it was not a good year. Tunisia was boring in general, Sfax particularly so.

BLVR: You write that there were a series of high-profile art forgeries that occurred in Europe before and immediately after the Second World War, including the cases of Han van Meegeren and Icilio Joni. Were these events considered major cultural touchstones among writers, artists and academicians?

DB: Absolutely. Art forgery was a hot topic in 1950s Paris, especially among the crowd of art historians that Perec fell in with in 1955-1956.

BLVR: How influential do you think were van Meegeren and Joni in the conception of Perec’s novel?

DB: Perec had a very good eye and it is no coincidence that the first words of his first published novel are “The eye, first of all…” But in painting as in prose, a good eye is not enough to tell you whether what you see is real or fake. Perec’s later use of hidden quotations (in Things, A Man Asleep, Life A User’s Manual) has to be seen in this context, which is an artistic one at bottom.

BLVR: Did the criminal underworld hold a special fascination for the young Perec? I was particularly intrigued by the invocation of Fantômas in Condottiere.

DB: I think you can safely assume that the mention of Fantômas in Le Condottiere is a reminiscence of a childhood comic. Perec read detective novels in his teens, to be sure, and his last unfinished work, 53 Days, is a mystery, or as the French say, un thriller. (N.B., It’s just been reissued in paperback by Godine). However, nothing in his work touches on the low life that attracted Bataille, Genet, and so on. What interested Perec was deception—deception as art, first of all, and in an ancillary way, deception as crime. The first version of the novel that eventually became Things, titled The Great Adventure, is about a heist planned by market researchers with data-sorting skills. Among the many stories of Life A User’s Manual there’s a grandiose attempt to sell the Holy Grail, a sophisticated trick that makes the Devil appear, and maps forged (or misread?) to prove that Columbus did not discover America. Those are the kinds of crime Perec invented and wrote about. He’s really not into violence or squalor or drink or the “hard-boiled”.

BLVR: What about any parallels with film noir?

DB: Yes, Perec did go to the movies a lot as a young man, but with just a few exceptions, he did not like French films in general, was pretty harsh about the New Wave, and thought Jean-Luc Godard was a fraud. When he had finished making [the film] A Man Asleep with Bernard Queysanne, Perec quipped that they’d made a film neither of them would think of going to see. And it was true! They used to watch videotaped Hollywood musicals together, not art movies. He would have liked to be involved with cinema much more but only one of the scripts he rewrote or wrote dialogue for made it to the screen [Série noire, 1979].

III. A “FALSE NOSE”

BLVR: Reading Condottierre now, I wonder if the book is one of the first to belong to the metaphysical detective genre, which became so popular beginning in the late 50s and early 60s?

DB: Condottiere demands a lot of attention, and was hardly likely to make its way in the world through reader-appeal alone. It is experimental in form, but not in the same way as the recent “new novels” of [Alain] Robbe-Grillet, [Michel] Butor and [Nathalie] Sarraute. And, to be blunt, it was not original or powerful enough to overcome on its own all the hurdles that stand in the way of a debut novel. Its interest, qualities and importance really are easier to see with the hindsight we now have.

BLVR: One of the other themes that peaks out immediately in Condottiere is this exploration of boredom, or what he later called the “infra-ordinaire”, which carries all the way through Perec’s career. What about boredom is so important to understanding Perec’s very French perspective?

DB: I would rather put Perec’s investigations of the quotidian and the ‘infra-ordinary’ under the heading of fascination, not of ennui. He shows that the normally unnoticed fabric of existence is quite entrancing, if you learn how to look at it properly. In the 1950s, to be sure, he was bored, like the teenager that he was, and he played far too much pinball. Once Perec’s own artistic project got off the ground with Things, I’d say he was a writer who taught us all how not to be bored. Speaking for myself, I don’t find Perec’s perspective “very French”. Nor more than I find Beckett “very Irish”.

BLVR: The character of Gaspard Winckler, who appears in two other texts by Perec—W, or the Memory of Childhood and Life A User’s Manual—is introduced in Condottiere as both narrator and, we suspect, Perec’s alter ego. To what importance do you ultimately give this three-headed figure in Perec’s world of narrative puzzles?

DB: I am not at all sure that Gaspard Winckler is a character! The name crops up in several other places too (for example, in a film adaptation of Things that was never made), and if you wish you can treat it as what the French call a “false nose”, a transferable pseudonym, like a paper hat passed around among guests at the dinner table. However, the earliest Winckler, in Condottiere, is motivated by rage, and the last one, in Life A User’s Manual, is said to have patiently and meticulously plotted a revenge that is not yet complete. If you want, you can take the two as stemming from the same anger, and attribute that aggressive emotion to the hidden author of both, and by doing so plunge yourself into an Oedipal (or anti-Oedipal) reading of Perec’s entire literary project. But I stop short of doing that. Perec’s defenses are higher than any I can climb.

BLVR: Over the last three decades, the English-speaking world has been treated to all sorts of Perec treasures due to your insightful translations. Does anything else remain of Perec’s canon that we haven’t seen as of yet?

DB: I really ought to say no, that’s it folks, but maybe one day a translator of much greater genius than mine will find a way of Englishing:

1. Alphabets (176 heterogrammatical sonnets)

2. Mots Croisés 1 and 2 (books of elegant brain-teasing crossword puzzles)

3. There is also one (not really finished) novel and a clutch of short stories written in the 1950s that remain unpublished in French.

4. A handful of articles (included book reviews) not translated into English so far.

5. Two German radio plays that are not even translated into French (and I would not want to try).

6. Whoops, I nearly forgot: two stage plays, L’Augmentation and La Poche Parmentier, which I did translate years ago, but nobody wanted to publish them.

7. Half a dozen film scripts in which Perec participated to some degree (one of them, an adaptation of Things).

8. A substantial number of lectures and talks collected in Entretiens et conférences.

9. Not to mention the correspondence, of which a good selection is available in print in French (mostly from the 1950s and 1960s, before Perec had a telephone).

But after that I think you really would be down to the laundry list… so that really is it!

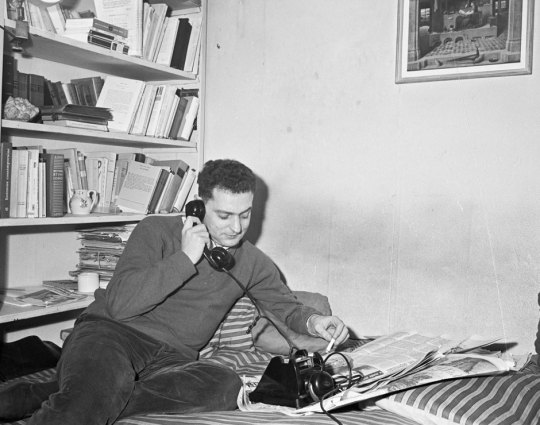

Photograph of Perec: Jean-Claude Deutsch/Paris Match via Getty Images