In 1930, Harry J. Anslinger was appointed the first commissioner of the newly founded Federal Bureau of Narcotics. It was a major promotion for the 38-year-old former Pennsylvania Railroad investigator, and he didn’t intend to squander it. But Anslinger was stepping into a precarious situation and he knew it.

The Bureau of Narcotics was an outgrowth of the Bureau of Prohibition, the federal agency tasked with enforcing the nation’s ban on alcohol. But the war on booze was in its death throes, and the agents staffing the Bureau of Narcotics, largely drawn from the Bureau of Prohibition, were a baggage-riddled bunch, venal and demoralized.

With the new agency’s meager budget and unclear raison d’être, there was little to suggest a course correction. Anslinger quickly realized he had to give his fledging agency a worthy cause to justify its continued existence and galvanize a listless force. With alcohol all but legalized, Anslinger set his sights on two new scourges: marijuana and heroin.

Late one night in the fall of 1933, a young man named Victor Licata used an axe to murder his parents, two brothers, and a sister in their Florida home. Early police reports suggested he was a heavy marijuana user, and the press seized on the chance to sensationalize a grisly crime. Soon the so-called “axe-murdering marijuana addict” embodied Americans’ worst fears about the risks of cannabis use.

Crafty and opportunistic, Anslinger watched the public frenzy surrounding Licata. He observed how marijuana could serve as a kind of vessel for paranoia, subsuming sentiments that might otherwise float freely in the ether—ideas about disorder, subversion, and youth run amok. Anslinger wondered if he couldn’t leverage that symbolic power to crystallize his new agency’s cause. In the midst of the media maelstrom, he used Licata’s rampage as one of the first entries into what became known as the “Gore Files”: articles drawn from police reports detailing heinous crimes allegedly committed under the influence of marijuana.

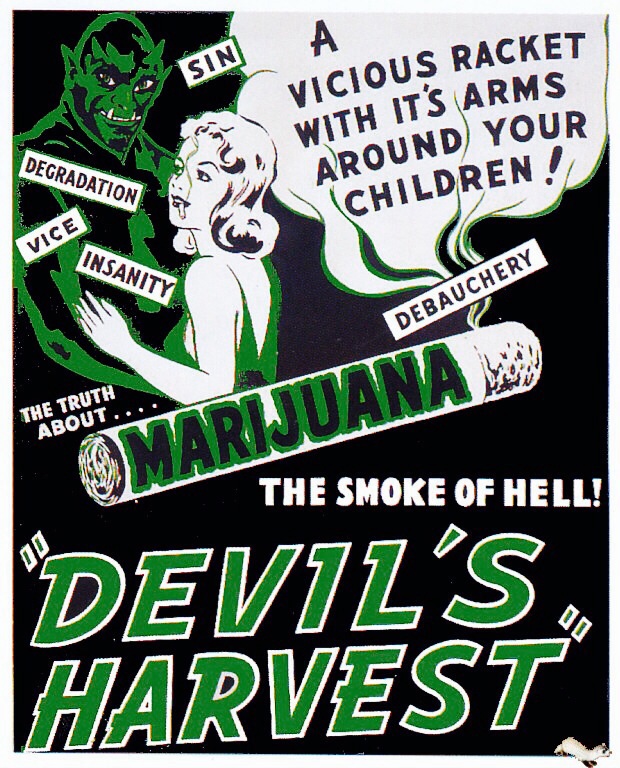

For most of the 1930s, Anslinger collected these stories and used them with the flair of a PR mastermind. Utilizing his connections at national newspapers—including a close friendship with publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst—he turned police blotters into lurid tales of young people transformed by marijuana cigarettes into murderers, rapists, and thieves. Other “files” include the alleged case of a lesbian stabbing her lover in a row over marijuana use and two girls from New Jersey who got high and shot a bus driver to death over a $2.40 fare.

Anslinger eventually published 200 of these stories in newspapers and magazines, wielding a powerful command over public opinion at the time. That 198 of the 200 crimes recounted in Anslinger’s Gore Files were eventually discredited as the result...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in