In 1976, my sixth-grade language arts teacher Mr. Larsen—a small, swarthy, and pudgy man with a heavy black mustache—announced our class would be putting together a one-off school newspaper to be distributed among all the other students at Green Bay’s Allouez Elementary. The kid whose dad edited the city’s daily paper was named editor-in-chief, and against my better judgment, I was named entertainment editor.

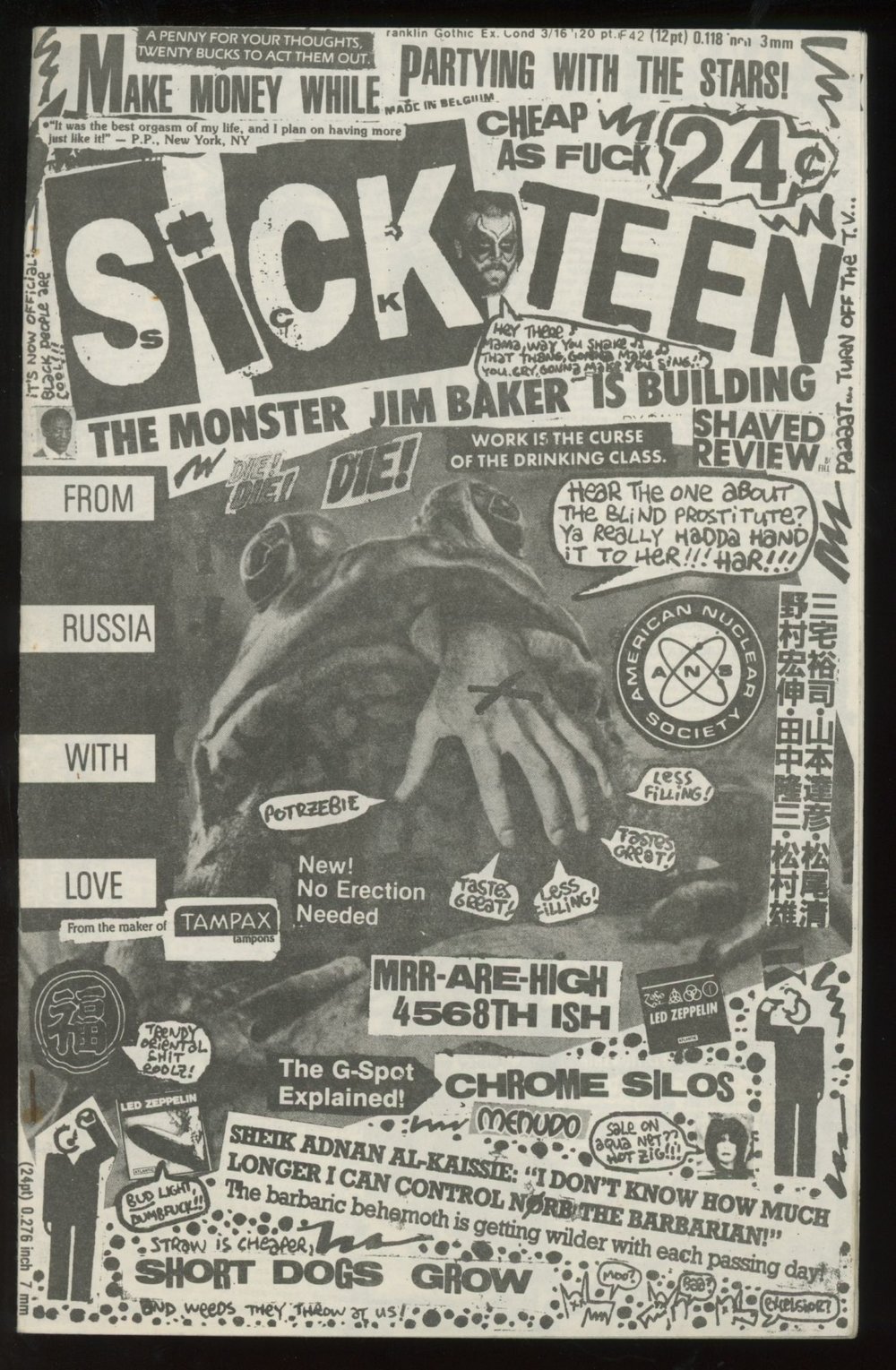

I recall receiving a handful of submissions from classmates for the small section, but four decades on now I only remember one of them clearly. Nørby Rozek turned in an obsessively-detailed, graphic, rambling, and hilarious review of Ralph Bakshi’s animated fantasy film Wizards. The review ran twelve pages. Only trouble was, the entire paper was only slated to run eight pages. Even back then, I remember thinking the piece had a preternatural flow and rhythm to it far beyond what you’d normally expect from an eleven-year-old. Trying to edit it down to size seemed almost criminal.

I didn’t know it at the time, but that review was a portent of things to come.

I’d known Nørby (aka Nob, aka Nubby, aka Orb, aka Orbit) since first grade, maybe earlier. A tall kid with a bit of a paunch and owlish glasses, Nørby was a determined, maybe even genetically-predisposed outsider. In grade school, his wardrobe consisted of deliberately and garishly mismatched clothes. A gifted artist and math prodigy, he spoke at a breakneck Walter Winchell clip, and peppered his speech with references to Sixties bubblegum pop, commercial jingles, comic books—Ronco and Wham-O products, Star Trek, and other trash culture ephemera.

He was, in simple terms, an eccentric genius (a word I try to avoid at all costs) whose brain absorbed and stored everything it encountered in the lower wavelengths of the cultural spectrum.

By 1984, in any small town in America, it’d be possible to find a couple disaffected kids with funny haircuts and torn jeans in a garage, banging out three chords on their guitars as fast as they could manage while screaming about Reagan and the Moral Majority. Four years earlier it was a different story.

After The Sex Pistols imploded in 1978, punk began evolving into a leaner, much louder, much faster guise dubbed hardcore. By 1980, the fledgling hardcore punk scene, dominated by bands like Black Flag, Minor Threat, and The Bad Brains was focused almost exclusively on the coasts, particularly Washington DC and Los Angeles. To this day and to a lot of people involved in the scene, that perception remains. Most paid no attention to what was happening in the middle of the country.

No surprise then that by 1979, Rozek—who was rail thin, had cropped his hair, had...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in