There wasn’t a word for what happened in my life, a way to describe it, though there were adjectives that came close, like “obscene,” as one friend astutely put it. I hadn’t even known it was possible, let alone legal. No one could relate. No one knew how to talk about it. No one, except for one protagonist—the narrator of Constance Debré’s Love Me Tender. In the novel, the protagonist becomes an outlaw mother, a term inspired by a passage from Adrienne Rich’s 1976 text Of Woman Born. The outlaw mother is someone who makes decisions for the sake of her own autonomy and personal fulfilment, believing these to be necessary conditions for her child’s happiness.

I’ve seen motherhood from many disenfranchised sides: First, I was a devoted stepmom, then I was a stepmom experiencing unexplained infertility. And finally, an estranged stepmom trying to queer family-create. There aren’t any Hallmark cards for mothers like me. I have come to realize, though, that if you seek hard enough, there are books. Turns out I’ve been collecting them since I was a teenager, before I knew what the future would hold.

In the spring of 2023, I left my husband after spending six years with him and my stepdaughter, whose biological mother I coparented with while he was on tour for over half of every year. When I learned about his double life—he was sleeping with prostitutes and abusing cocaine as I was undergoing infertility treatments—my decision was easy. However, I naively thought that even if we divorced, I’d continue to see my stepdaughter—someone who had formed a deep attachment to me and vice versa. I didn’t realize I could be banned from seeing her and threatened with legal action if I didn’t have zero contact with her. I was reeling, blindsided, manic with pain.

Aside from the no contact with my stepkid rule, which was further cemented every day—everything in my life improved in an almost exaggerated way once I left my marriage. I sold two books, loved my living space, and my finances and friendships thrived. By the time Love Me Tender was recommended to me, I’d already lived a juicy handful of months feeling the freedom and authenticity my divorce afforded me. Yet it was also deeply obvious that I was being punished for said freedom—because freedom for women who leave their societal roles doesn’t come without punishment.

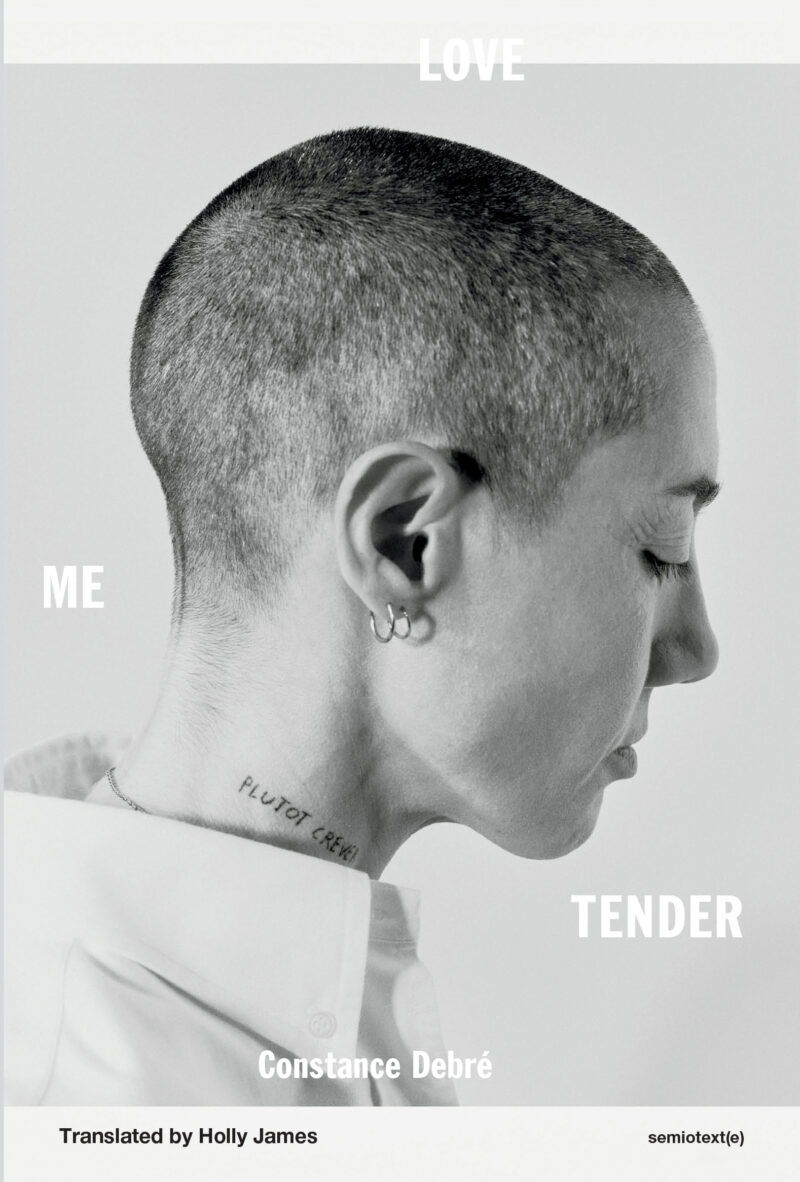

Love Me Tender, translated from French by Holly James, is a short, sparsely written book in the middle of the author’s autofiction trilogy (though on Instagram, Debré has facetiously said the books are not autofiction and not a trilogy. They are just the order she wrote them in). Love Me Tender was originally published in 2020, but it wasn’t translated into English until 2022. In the vein of Eileen Myles and Sheila Heti, Debré names the protagonist after herself. The first book in the series, Playboy, handles the fall-out of Constance leaving her marriage and prestigious life as a lawyer to date women and pursue writing. In Love Me Tender, Constance has been mostly seamlessly coparenting with her ex-husband for a few years, until one day he tells her that their eight-year-old child hates her and doesn’t want to see her anymore. From here, things escalate in unimaginable ways: Constance’s lesbianism, and even the books she owns, are used against her in court, so that she is only allowed to have supervised visits with her son.

Nine months go by. “Like a pregnancy but the wrong way around. A birth in reverse.” she writes.

When my stepdaughter and I were living together, she was the person I discussed films and books with, jumped into pools with, saw plays, and cooked farro bowls with. We’d picnicked in Paris, gone boogie boarding in the ocean, fought about cleaning her room, hiked in the Red Rocks, and I was with her when she learned to ride a bike, lost a tooth, and learned to swim. She was in my life from the ages of six to thirteen, the same ages I used to see listed on her LEGO boxes. We celebrated Stepmom’s Day every May. She used to run toward me, throwing her arms around my body and ask to have “reading parties.” We spoke a shared language. Her pajamas, sweatshirts, and books are still mixed in with mine. How do you go from packing lunches and driving to school pick-up to being blocked on iMessage overnight?

“What is this insane world I’m living in? This world where love is transformed into silence even without death?” the protagonist writes.

The reasons I was kept from my stepdaughter? Unclear. They felt like desperate attempts at control—just as they are in Love Me Tender—because I wrote queer books, had gay friends, had once gotten my stepchild a green smoothie instead of something savory, and that I originally hadn’t wanted the dog we’d by then had for three years. After being a person who signed permission slips and flew out of the country with my stepdaughter, I now wasn’t allowed to text, call, say “Merry Christmas.” I was told not to go to her plays, a rule I ignored. I was the one being punished for my ex-husband’s behavior. There was no justice, no logic, only a gruesome reality.

I’ve dated more than a handful of women in the past two years, and three of them were moms, all divorced. One of them, who had a seven-year-old son, told me that after she read Love Me Tender, she had to immediately get it out of her house and put it in the foyer of her building. Another, who had not read the book, said the following, in reference to the experience Constance and I had been through, “You’ve lived through my worst nightmare.” My own mom, when I pushed the book into her hands in the fall of 2023, described it as “sad.”

For me, the book wasn’t sad, though, it was a bible, a high-wire act, my best friend. The people I’d demanded read it hadn’t lived through what I had. It would make sense that the book would isolate other people, the same way that the experience had been isolating for me. Constance is polarizing. She makes people around her uncomfortable. And I noticed that when I gave the book to people to read, telling them it was the only story that felt relatable, that that made them uncomfortable too. I thought the book would open up conversations, but it seemed to close them, instead.

Debré writes: “I avoid parks, schools, bakeries at half past four in the afternoon, I take detours, I hide away on weekends, I wear sunglasses even when it rains.”

I avoided: Trader Joe’s, the school bus down my street at 3pm, miso ramen, farro, the pad thai place, Gilmore Girls, airplane movies like 10 Things I Hate About You and Freaky Friday, the YA section of the bookstore, and the part of my closet that still had her sweatshirts, pajamas, and dresses. My Gmail login still defaults to hers, no matter what I do. The googly eyes she’d put on all my Picasso prints one April Fools’ Day are still hanging on.

The protagonist of Love Me Tender and I both left the role that makes people the most comfortable in this world: a woman who lives with a man and takes care of their child. Not only did Constance become gay when she left (her words)—she began writing books—and worse? Dared to take said writing seriously.

Is anything more threatening to society than someone who writes honestly? I tell my students that the only place I’m free is my writing; it’s the only place no one can tell me what to do. And yet, not only must certain mothers endure the unendurable, we are also told not to write about it. We should suffer, and we should also stay silent. I’ve had friends tell me to “lay low.” I turned down publishing anything about the situation for two years.

Constance writes:

“They tell me not to publish the book, they tell me not to talk about girls, they tell me not to talk about fucking, they tell me I mustn’t do anything to hurt Laurent, they tell me I mustn’t shock the judges, they tell me to give myself a pen name, they tell me to let my hair grow, they tell me to become a lawyer again, they tell me to stop getting tattoos, they tell me to put on make-up, they ask if that’s it now, no more guys, they tell me to try and talk to him, they tell me he might have taken things too far but it can’t be easy for him, they tell me it’s only normal for my son to push me away, they tell me a child needs a mother, they tell me a mother can’t exist without her son, they tell me I must really be suffering, they tell me I don’t know how you do it, they tell me, they tell me, they tell me.”

If Debré’s novel was to take us on a hero’s journey, Constance would reunite with her son, now a teenager: they’d heal, they’d process, they’d be in therapy, they’d live together again. Instead, Constance wakes up one day and describes the pain as not being raw anymore. She compares it to waking up one morning and your flu is suddenly gone.

Constance is decidedly not a victim. She surrenders. She doesn’t take on the altruistic mindset of American mothers, such as: I’ll do anything to fight for my child! A few of the people who have read the book tell me, I would have kept fighting.

The most outlaw thing a mother can do is not mother. I spent months where I only ruminated. I spoke in circles to anyone who would listen. I tried begging, pleasing, bartering, manipulating, coercing. I had sessions with a blended-family therapist.

“Waiting for the book to come out, waiting for the court case to start moving, waiting for a bit of cash to come through, waiting to see my son again. Waiting for things to calm down, for the universe to adjust, to heal, to rebuild itself. My universe. I won’t go back, I won’t climb back into my old skin.”

During the peak of my struggle, a friend told me about a play by Bertolt Brecht, The Caucasian Chalk Circle. In it, she explained, two women are fighting over who the “real” mother of the child is. The child is in the middle, and they both pull them in different directions. Eventually, one of the mothers walks away, and she is the one deemed the “real” mother.

It wasn’t until the end of Love Me Tender, when the narrator begins surrendering—which is different from giving up—that her other relationships are finally able to move forward and her life begins to coalesce, progress.

Our culture hates when mothers stop thinking about our children all the time—we are supposed to live as martyrs, stay devoted to them, hold tight and never let them go, at the risk of our own mental health. But, like Debré writes on the final page, sometimes “there aren’t that many different solutions.” Sometimes the answer isn’t action, it’s lack thereof, and stepping out of the patriarchal institution of motherhood, as Rich advocated, can lead to empowerment. Watching a woman self-actualize, find her agency and empowerment may just be, in certain situations, what is better for the child.

I still send texts to my stepkid, books for her birthday. It’s like conversing with a ghost. The narrator of Love Me Tender, was, for me, a depiction of a person who had survived my own worst nightmare, a nightmare so improbable I hadn’t even known to imagine it. And after two years of being heartbroken and inchoate, I would also survive. What’s more, maybe now the other outlaws will find me.