It was Oscar Wilde who said that “the first duty in life is to assume a pose. What the second is, no one has yet discovered.” My pose at Campus Crusade’s 2024 Winter Conference in Anaheim, California, was the following: After two decades ensconced in godless academia, I was back to reconnect with my roots, to revisit the scene that had made me, to see what light the current evangelical movement could shed on Trump’s America. Studying the schedule at a convention center down the road from Disneyland, and surrounded by kids half my age, I felt like a double agent, which is exactly what I was, in a sense. I’d spent a decade of my life as an evangelical going door-to-door for Jesus and appearing on Christian radio, and years as a Bible study leader in the most powerful evangelical group you’ve never heard of, the group whose leadership played a central role in ending Roe v. Wade and influenced the decision to invade Iraq. Now a credentialed member of the secular humanist establishment, I was everything I had been raised to believe was wrong with America.

I am what has become known as an “exvangelical,” a loosely defined identity group that first emerged after Trump’s 2016 election that is composed of young people who are unhappy with the church’s embrace of militarism, along with its war on science, women, and queer people. While our exact numbers are unknown and our electoral impact is as yet unmeasured, exvangelicals are the vanguard of what pastors Jim Davis and Michael Graham, in their 2023 book, The Great Dechurching: Who’s Leaving, Why Are They Going, and What Will It Take to Bring Them Back?, called “the largest and fastest religious shift in US history, greater than the First and Second Great Awakenings and every revival in our country combined… but in the opposite direction.”

Inside the convention hall, there were a thousand-odd seats, two camera pedestals, and a stage flanked by two large video screens. A clock on the screens counted down the minutes until the start of the first event, blandly titled “Session 1.” Christian anthem rock by an artist I didn’t recognize played over the sound system.

With less than a minute to go, the song abruptly switched to Tones and I’s “Dance Monkey.” The air shifted and I watched in awe as the doors to the ballroom were pried open, unleashing a flood of college students like a Civil War reenactment sponsored by Vans. The first skirmishers through held the doors open for a column of flag bearers. The University of Arizona was first, followed by Utah, Boise State, then Oregon State, then several flags I couldn’t make out. The floor was soon awash in a sea of wholesome twentysomethings. I immediately recognized the evangelical look from my high school days: hoodies, black jeans, skate shoes, and messenger bags. I spotted several T-shirts of the officially approved Christian bands from my youth: Switchfoot, Jars of Clay, and P.O.D. The racial makeup looked to be 90 percent white, with occasional Asian American and Black students breaking up long lines of blond hair. The Oregon State flag bearer posted himself two rows away and climbed atop a chair, whipping his black-and-orange flag back and forth, as if he’d just stormed the ridge at Gettysburg.

The bedlam continued for several minutes before everyone rallied around their respective flags. Then a five-piece worship band mounted the stage and began what would turn into a rousing thirty-minute praise-and-worship set. They opened with “Praise,” a drum-heavy anthem by a Charlotte, North Carolina, collective known as Elevation Worship. Soon enough, a substantial portion of the crowd was singing with their hands held aloft, as if to signal some sort of spiritual touchdown.

The words rang out, the drums thudding in my chest.

Let everything that has breath

Praise the Lord

Praise the Lord

Defenseless against the energy of the room, I was soon singing along, my hands in the air. I’d left this scene behind long ago, and yet through nostalgia’s odd alchemy, I saw that nothing had changed. It was 1989 again. I’d had my fair share of life chapters: I’d joined the Marines, gone to grad school, moved to Mexico, worked as a war correspondent, been blown up by a roadside bomb, been diagnosed with PTSD, published two books. Yet a part of me remained that same scared kid who’d given his life to Christ at a beach bonfire years before. Lonely and wide-eyed, the future little more than a slogan printed on a public library poster: THROW OFF THE BOWLINES. SAIL AWAY FROM THE SAFE HARBOR. EXPLORE. DREAM. DISCOVER.

For the longest time I’d looked at my evangelical years as something like a phase. I’d come of age in the Reagan era, just as evangelicalism was becoming a major force in American politics. While I’d personally found Christianity noxious for many years, for my friends who’d remained, I had come to view the religion as similar to Douglas Adams’s description of Earth in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy—“mostly harmless.” Now, in the Trump era, with the rise of a militant Christian nationalism whose leaders frequently describe Trump as a leader anointed by God and “an imperfect vessel for God’s perfect will,” it was starting to sink in that the religion of my youth was, among other things, a handmaiden to fascism.

These days, I teach at a supersize American university where many of the professors come from elite colleges in the Northeast, and whenever my past comes up in conversation and my colleagues discover that I used to be evangelical, things can get a bit weird. I did a stint in the Marine Corps before going to grad school, but somehow the idea that I had been a Bible thumper strikes them as infinitely stranger and more incongruous. I have learned to mostly ignore their incredulity over the years, sometimes dismissing my past as something like a drug phase, which it was, in a manner of speaking. (During my Crusade years I was repeatedly told that it was highly desirable to be “drunk on the Holy Spirit.”)

I left the church in the late 1990s, along with my best friend from college, but it wasn’t until he died of a sudden heart attack in 2022 that I finally felt free to reexamine my religious past. For reasons I’ve never understood, Ryan had quietly drifted back to Jesus after college, and, out of a sort of misguided politeness, we’d stopped talking about that part of our past, focusing instead on our replacement religion of surfing, a pursuit that seemed capable of delivering the same type of mystical highs as organized religion but with the added benefit of actually being fun. But with Ryan gone, I felt an urge to figure out what my lost faith had been about and what it had done to me—and by extension what it had done to America. In grad school, I’d come across a line from Jane Austen’s Persuasion: “She had been forced into prudence in her youth, she learned romance as she grew older—the natural sequence of an unnatural beginning.” In my fifties now, my prudence discarded long ago like an old letterman’s jacket, I decided to look at my unnatural beginnings for the first time.

This is how you convert people to Christ: You take them to the beach, you build a fire, you invite a bunch of pretty girls, and you make sure that at least one guy with a guitar and a solid handle on some uplifting Jesus-based songs is there. Then, as the sun starts to set, and you’re swimming in beauty and wonder, and you’ve sung some songs glorifying Him—maybe something by Keith Green or Michael W. Smith—you tell everyone to break off into pairs and go pray.

I don’t remember the name of the girl who chose me as her prayer partner, but I do remember that she was nicer to me than any girl had ever been before. In a week, I’d be starting my freshman year of high school in suburban San Diego. She was a junior there, and I needed all the friends I could get.

“Heavenly Father…,” she began, eyes closed. She was speaking in the soft flower-petal tone that Christians use when they pray out loud. “We just want to thank you for the gift of this beautiful day…”

After we finished praying, the group reconvened, drawing closer to the fire as darkness fell around us. The guy with the guitar started up again, explaining the process by which one could accept Jesus into one’s heart and make Him one’s personal savior. For a teenager growing up in Southern California, there were so many dreams on offer (Top Gun, the Navy Fighter Weapons School, was down the road from my house), but none were so powerful as the dream of belonging.

And so I did what kids usually do: I followed the group. I accepted Jesus into my heart.

There were no thunderbolts, no visions, no saints with flaming swords in the sky, no brass trumpets echoing across the heavens, only a vague churchy feeling that started in my chest, catching in my throat. I closed my eyes, and after thirty seconds or so, the spell was cast. I was the property of Jesus.

It was 1985, the height of the Reagan era, and a rough time for my family. My parents had divorced three years before, and the harsh economic realities of being a single mother with three young kids were starting to settle over my mom. At times it felt like life itself was collapsing on us, the hand of fate squeezing us, as we’d been forced to move from a beautiful four-bedroom house at the edge of a canyon with a stream running down it, to a cramped condo on a busy street.

Shortly after moving, my brother Dan and I had launched a multipronged grow-up-quick scheme that involved us covertly subscribing to Playboy magazine (beating Mom to the mailbox was crucial) and shoplifting cigarettes and porn from a local liquor store whose owners seemed indifferent to the miracles of the modern security camera. Dan and I talked frequently about how to score weed. LSD remained a far-off dream, like the Himalayas. A budding delinquent with an adrenaline streak, I gave a sermon in the form of a dare to my circle of BMX-riding friends: I would steal anything from the local organic market and sell it to them at half price.

Anything, I emphasized. Anything.

I was tough, mind you. An inside linebacker in the local Pop Warner league who’d grown up backpacking in Oregon, I’d been nourished on military legends spoon-fed to me by my Vietnam vet dad and a neighbor who was an instructor at Top Gun. Really, I was a white kid ignorant of consequences. I’d been swaddled in the blankets of suburbia and yet a fire burned inside me, lit by the spark of my parents’ divorce. Nobody could hurt me. Nothing was my fault. I was ready to take life head-on. Punch its headlights out.

A few years before my freshman year, my older sister had been invited to a beach bonfire hosted by Campus Crusade, followed by my brother. A gifted wrestler and varsity football player with near-perfect grades, my brother was quickly identified as a leader by Crusade staff. He was the perfect fit for Crusade’s “key man” strategy, by which they cultivated role models on campus and watched as the student body proceeded to follow their shining example to the Christian faith. My sister left the group after a few months, but by the time I began high school, my brother had risen in the ranks of Crusade and become a student Bible study leader, presiding over long sessions every Wednesday night in our tiny living room.

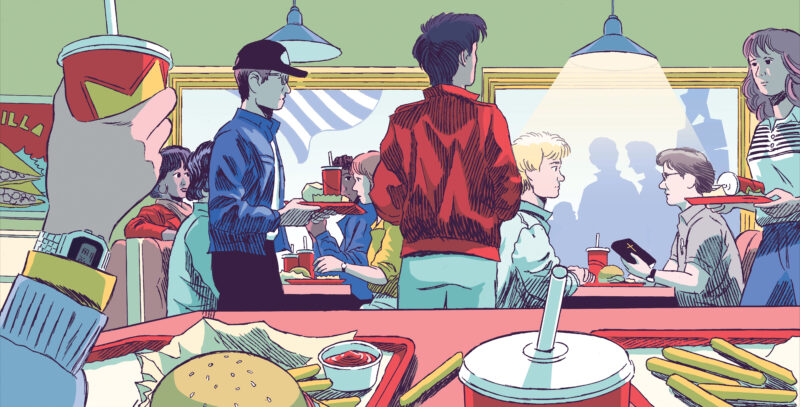

Not long after the beach bonfire I attended, an adult Bible study leader from Crusade named Mike picked me up at my house and drove me to a nearby strip mall with a Carl’s Jr., a fast-food restaurant favored by Crusaders because the founder of the chain was an ardent supporter of various pro-life charities and made sure that a large American flag was flying at every location. Seated in a booth, I looked around, staring idly at the families surrounding us: older sons in their oddly authoritative Members Only jackets (this was the ’80s, mind you); younger sons looking tortured and trussed-up like draft horses in their orthodontic headgear; middling, perpetually grossed-out and bored daughters sporting exquisitely large updos—hair lifted and arcing heavenward in a victorious topiary hedge sculpture as if to celebrate the sheer, unfettered Technicolor abundance of America.

Against all this cultural white noise sat Mike, a veritable bulwark of Midwestern restraint, armed only with his weathered polo shirt, metal ballpoint pen, and a fresh copy of a Campus Crusade pamphlet known as the “Four Spiritual Laws.” To look at Mike was to take in a straightened version of America where the ’60s had never happened, something I would later learn was no accident but was, in fact, an expression of Crusade’s personnel policy and its grand vision for the world—a pre-feminist, pre-Roe, pre-Vietnam, Disneyfied America dominated by nuclear Leave It to Beaver families. Crusade was many things—a youth group, a social experiment, a Christian madrassa system—but at its core, it reflected the larger project of evangelicalism, which is to say it was a time machine fueled by a kind of nostalgia for a lost America that had never really existed. Back then, my impression of Mike was that he was something of a spiritual trainer, a coach putting a team together.

Because my eternal fate was at stake, Mike needed to make sure I had all my various celestial boxes checked, and as we sat there, wreathed in the smell of burger smoke, he walked me through Bill Bright’s pamphlet version of the Gospel. (Law 1: “God loves you and offers a wonderful plan for your life.”) This was, I would later learn, completely in keeping with Crusade’s vision of itself as a Jesus-based guerrilla unit operating behind enemy lines, one that was “in the world, not of the world.”

We said a brief prayer together, the awkward seconds ticking by, transformed by a sort of Bible-based magic into nervous holy expectation. All that was, all that is, all that would ever be ripped through my heart like a righteous tornado, sweeping me and all my dreams up into the sky. Technically, I’d been saved at the beach a few days before, but because this meeting was presided over by an adult, this time felt extra official.

My immortal fate secured, Mike explained to me that a freshman Bible study was starting up and asked if I’d like to join.

Looking back, I can see that Mike was asking me something else. This was a threshold moment, like someone handing you a pen to sign military enlistment papers. To balk now would be to court rejection by my brother and, by extension, my family. High school was a place crowded with invisible rules, the violation of any one of which threatened ostracism. The only rule I knew for sure was the obvious one: in the wilderness of high school, you needed a pack to run with.

As I would later learn, Campus Crusade for Christ was a student movement modeled in part on the very communist groups it opposed, groups that began with small, ideologically committed cells that would serve as cadres for the inevitable revolution to come. In order to withstand the threat of godless communism, America needed Christian kids with a case-hardened dedication to struggling against a belief system that threatened the very fabric of the nation.

Mike wasn’t just asking me if I wanted to attend a once-a-week Bible study. He was asking me if I wanted to join an army, to become an insurgent, a revolutionary for Christ. Because he knew Dan, and knew that I was just a younger version of him, he surely knew the likelihood was high that I’d want to join. Looking back, I sometimes wonder if Mike might have seen me for who I actually was: a bad kid who wanted desperately to be good, a kid whose broken home had left him open to whatever huckster happened along.

He was asking me if I wanted to have a crew, if I wanted to belong.

I nodded and told him I did. More than anything.

Bible study, led by Mike, was held at another student’s house, a junior-varsity water polo player named Steffan. There were ten of us, all freshmen from good homes, impressionable as balls of Play-Doh. Most of us were athletes, though I was the only football player. Steffan’s mother, who was from Sweden, baked a plate of cookies each time. I went every week for the entire semester, hungry for Steffan’s mom’s cookies and hungrier still for the Word of God. I could feel my life coming into focus.

That fall, Steffan and I started attending a local nondenominational church that met in an elementary school auditorium, and we talked frequently in his bedroom about the Bible and how to improve our walk with Jesus. I’d been a Christian for only a couple of months, but my previous life as a shoplifting punk seemed like it had been lived by a completely different person, a person I recognized as misguided, lost, and spiritually dead toward God. In Jesus I’d found something real and enduring. Just sitting down and reading the Scripture made me feel like I had been given access to the secrets of human existence, and that the author of the universe was smiling down upon me, despite my zits and my mustard-gas breath.

In December, my Bible study went to the annual Winter Conference at Campus Crusade’s world headquarters at Arrowhead Springs, a luxury resort in the mountains above Los Angeles that in its heyday had been a playground for Hollywood deities like Elizabeth Taylor and Humphrey Bogart. A weeklong program of carefully staged sermons, training seminars, and sing-alongs, it was like the annual sales convention for Jesus Incorporated. My conference admission was paid for by my parents and a Christian English teacher who’d taken an interest in me, and it was my first encounter with the stagecraft and high production values of a faith that took its cues from the movies as much as from the Bible.

Campus Crusade for Christ (now known as “Cru”) is one of the largest parachurch organizations in the world, comprising an evangelical empire that stretches across the globe with more than nineteen thousand staff members working in 190 countries, and an annual revenue of over $700 million. While its core mission remains to convert students to Jesus, Cru maintains a vast network of ministries and political influence groups, including FamilyLife and Athletes in Action, along with the Christian Embassy in Washington, DC. In 1994, Cru’s leaders cofounded the Alliance Defending Freedom, the legal advocacy group that successfully litigated the end of Roe v. Wade in 2022.

Founded in 1951 by Bill Bright, the clean-cut son of a cattle rancher from Coweta, Oklahoma, who moved to Los Angeles in 1944 to pursue an acting career, Cru has carried the stamp of Hollywood into the present day. When he was disqualified from the military draft because of a burst eardrum, Bright began working with a friend who owned a candy company. After several weeks, Bright bought out his friend’s stake, founding what would eventually be called Bright’s California Confections. The business was an immediate success because of Bright’s organizational acumen and indomitable drive for growth at all costs. It wasn’t long before he found himself living the high life: driving a convertible, dressing in expensive suits, and riding horses in the Hollywood Hills. When he wasn’t managing his growing business, Bright took acting classes at Hollywood Talent Showcase.

Though Bright had always been somewhat spiritually indifferent, the trajectory of his life was altered forever when he began attending the First Presbyterian Church of Hollywood at the urging of his landlord. It was the largest Presbyterian church in the US at the time, and according to the daughter of one of its former pastors, had “millionaires falling out of every pew.” Bright had stumbled into a hotbed of revivalist energy and was suddenly surrounded by wealthy businessmen who seemed to be enjoying all God’s blessings. Yet they all insisted that their relationship with Jesus was far more important than any of their worldly achievements. After a particularly powerful Bible study session where the topic of discussion was Paul’s conversion on the road to Damascus, Bright returned home, got onto his knees, and accepted Jesus into his heart.

Following his conversion, Bright began practicing street evangelism with the College Department of Hollywood Presbyterian, traveling to towns across Southern California with paper tracts wrapped in cellophane. As Bright would later write in his 1987 book Witnessing Without Fear: How to Share Your Faith with Confidence, he was at first “scared to death” of talking to others about Jesus, but after a few early successes (including a convert who eventually went to seminary), Bright discovered that he had a knack for communicating the basics of the Gospel to strangers. By August 1945, Bright had come to believe that God was calling him to the ministry.

In the summer of 1946, at the urging of Henrietta Mears, an influential Hollywood Presbyterian leader who had also mentored the mega-evangelist Billy Graham, Bright enrolled in Princeton Theological Seminary. Uninspired by the curriculum at Princeton, Bright eventually transferred to Fuller, a new seminary in Pasadena, which allowed him to keep tabs on his candy business, which had struggled in his absence. In time, however, Bright became disillusioned with theological studies, declaring to a friend: “I’m not going to be sitting here studying Greek when Christ comes!”

Like Mears and Billy Graham, Bright had become convinced that America was a nation chosen by the Lord to lead the globe in the struggle against godless international communism. After conferring with Mears, Bright sold his candy business and dropped out of seminary in order to start a nationwide ministry to college students. Bright envisioned this group as part of a crusade against communism and the growing secularization of college campuses, as “shock troops” in a Christian army. Echoing this militaristic theme, a colleague of Mears’s suggested the name Campus Crusade for Christ.

Similar to Billy Graham, another Christian hawk kept out of the military by a minor medical condition, Bright viewed his work as opening up a domestic front in the Cold War. Unlike Graham, who preached to the masses, Bright zeroed in on the American college campus as the key battleground that would determine the fate of the globe. In a bulletin promoting his new organization, he warned, “Communism has already made deep inroads into the American campus, and unless we fill the spiritual vacuum of the collegiate world, the campus may well become America’s ‘Trojan Horse.’” As American troops were fighting communism abroad in Korea with bullets and bombs, Bright saw his mission as fighting communism at home—with preaching and pamphlets. “Christ or communism—which shall it be?” Bright was fond of saying. For his first military objective, he chose UCLA, the “little Red schoolhouse” down the road from Hollywood Presbyterian.

Through the ’50s and ’60s, Bright’s campus attack strategy evolved into a curious mixture of public spectacle and what one Christian writer called “religion gone free enterprise.” Bright had an intuitive grasp of how to market to large groups of people and developed a dumbed-down version of the Gospel, which became the pamphlet I was introduced to decades later, “Four Spiritual Laws.” He also didn’t shy away from stealing the techniques of the enemy in his war against the moral permissiveness of the ’60s counterculture. One “Berkeley Blitz” in 1967, where six hundred Crusaders “invaded” the college campus on a conversion drive, featured a Christian stage magician named André Kole. After learning of the 1969 gathering at Woodstock, Bright came up with the idea for “Explo ’72” in Dallas, featuring a slate of popular musicians like Johnny Cash and Kris Kristofferson, intermixed with sermons by himself and Billy Graham. At this patriotic response to Woodstock, the South Vietnamese flag flew onstage, a conspicuous symbol of support for Nixon’s war in Southeast Asia. The event, which some dubbed “Godstock,” attracted eighty-five thousand high school and college students from across the nation.

As a youth organization unshackled by sludgy church doctrine, Crusade was uniquely positioned to shift its programming to combat the secularizing forces of any given era, a sort of religious avant-garde that was able to probe the front lines of the culture. With the end of the Vietnam War in 1975, it wasn’t long before “secular humanism” replaced communism as the main enemy in the broader culture war. Despite Bright’s claim that he’d “never been involved in politics,” the 1980s saw Crusade parroting Republican talking points centered on “family values” issues such as abortion, homosexuality, teenage pregnancy, and the poisonous influence of feminism. On the tactical level, this translated to abstinence rallies led by Crusade staffers like Josh McDowell, seminars discussing biblical gender roles, and the Christian view of the AIDS crisis, which many evangelicals interpreted as God’s punishment for the perversion of homosexuality.

It was at this stage, in an era dominated by Ronald Reagan’s Cold War and sexual paranoia, that I entered the ranks of the Crusade army. In time, I would come to see that I’d been a pawn, a demographic entry in the larger body count, a casualty of Bill Bright’s war for America’s soul.

To call Campus Crusade a cult feels like a cheap shot, a lazy oversimplification. We wore no robes; we wrote no blank checks to the group; we were never made to sever ties with our families and move to a compound in Texas to collect firearms and await the apocalypse. And yet as I learned over the course of my first Crusade Winter Conference, just months after joining, this was no run-of-the-mill church youth group—this was a movement, a Christ-centered combat unit committed to spiritual warfare, and as such I was expected to conduct myself as a chaste soldier, a radical evangelizer who would help light my campus on fire for Jesus.

Shortly after I arrived at Arrowhead Springs, things got serious. After softening us up with motivational speakers, some surprisingly funny skits, and hours of praise and worship sing-along sessions, the boys and girls were separated into groups and ushered into different buildings for a full day of talks about the biblical views of gender and sexuality, led by Crusade staffers.

Premarital sex, they explained to a room full of adolescent boys, wasn’t your average sin. It was a contagion that was polluting the nation, rotting it from within, aided by Madonna, George Michael, and a godless secular media. Further, as Christians personally selected by God to save America and, by extension, the world, we were now squarely in Satan’s crosshairs and should expect—expect? no! feel joyously validated by!—the parade of carnal temptations that would henceforth follow us to the ends of the earth. If we strayed, there would be consequences: AIDS, gonorrhea (if we were lucky and God was feeling especially merciful that day), teenage pregnancy, porn addiction—plus a variety of nightmarish scenarios limited only by the human imagination. What’s more, indulging in impure thoughts was, in God’s eyes, functionally the same as having actual premarital sex, so I was in far deeper trouble than I’d imagined. Resisting the devil, they continued, required a 24-7 system of restraint and responsibility between brothers, and if we wanted to be Christian leaders, we should seek out “accountability partners” to help keep each other from straying.

I left the seminar room in a daze of conviction. All those sexual visions, the lurid parade of adolescent fantasies that had captivated me since I was twelve, were permanently out the window now, banished until that shimmering honeymoon night when I could join my bride in holy matrimony. All those sexual thoughts I’d harbored over the years had wounded God deeply. So deeply. How could I have been so callous? So unmindful of my Creator, when all those tears were running down Jesus’s face?

As I would learn many years later, there is a substantial body of psychological research that indicates that if you’re trying to ruin sex for people and damage them for the rest of their lives, forcing them at a young age into a strict regimen of thought control and social surveillance, of the sort that Crusade was promoting, is a really good way to do it—and I now think, with the benefit of hindsight, that injecting this much sexual fear into teenagers’ hearts was not only unethical but genuinely evil. In his pioneering study of mind control in communist China, Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism: A Study of “Brainwashing” in China, the psychiatrist Robert Jay Lifton argues that “by defining and manipulating the criteria of purity, and then by conducting an all-out war on impurity, the ideological totalists create a narrow world of guilt and shame. This is perpetuated by an ethos of continuous reform, a demand that one strive permanently and painfully for something which not only does not exist but is in fact alien to the human condition.”

The problem with totalist movements like Crusade is that while they market themselves as wholesome youth groups, they often traffic in a warlike rhetoric that echoes the paranoia of the McCarthy era—a world divided into realms of black and white, good and evil, pure and impure. And as I learned at my first Winter Conference, you were either all in or you were all out. The last thing I wanted to do was disappoint my brother, Mike, Steffan, and the rest of my Bible study, so whatever doubts I may have harbored, inside I knew I had no choice—I was in. All in. I had to be.

My junior year Steffan and I were tapped to lead a Bible study of our own. My brother had graduated the previous spring and gone off to glory at UCLA, the birthplace of Crusade. God’s plan was working; new leaders were needed. To be chosen like this was to show everyone in my life that I was following in my brother’s footsteps.

This promotion came down from Mike as he was driving me to one of our customary Carl’s Jr. meetings one afternoon. “God has big plans for you and your brother. But Dan is gone now and it’s time for you to step up.” Weeks later, as I looked out over the bright young faces of my freshman Bible study, my fears for the future and my feelings of apartness dissolved. I was raising up the next generation of Christian men. For the first time in my life, I felt useful and important. I’d found my place.

The only problem with this was that it wasn’t true. I hadn’t really found my place, and with my brother gone, the pressure to perform and to live up to a certain Christian ideal was gone too. After the sugar high of my conversion, my faith hadn’t deepened, and I could feel myself starting to lose interest in Crusade’s version of Christianity, which at times seemed like a glorified pyramid scheme—the focus was always on numbers and bringing in new members to the group using the “Four Spiritual Laws.”

Steffan, by contrast, had embraced this ethos wholeheartedly, and began insisting that we forgo eating and spend our entire lunch period sharing our faith with our classmates instead. Crusade had stopped my shoplifting and cigarette smoking, but beyond that, it didn’t seem all that useful as a lifestyle. Mostly, it was a giant buzzkill, a police roadblock on the fun interstate. Added to this, I was struggling in math, a subject that had always been my brother’s forte. I’d long been seen as my brother’s protégé—an idea reinforced by Mike—but as the Ds and Fs piled up, I learned to recognize the look of disappointment on my teachers’ faces when they realized that, unlike my brother, I was no whiz kid.

By the end of my junior year, I’d been demoted to sophomore algebra, which I proceeded to flunk, mostly out of stark-raving boredom. (Let x find itself, I reasoned.) After word of this got around, Mike took me back to Carl’s Jr., which had long since lost any meaning as a restaurant and become an off-campus vice principal’s office. “Struggling in your classes isn’t a sin, but Christian leaders shouldn’t have report cards full of Ds and Fs,” he explained. Mike was reinforcing Crusade’s “key man” method: my life was supposed to be a beacon to others, a veritable lighthouse perched atop a rocky shore whose lamp cut through the fog of iniquity.

When I talked to my brother about this one day during a weekend visit to UCLA, he told me that learning wasn’t really the point. The point was the discipline itself—it was a way of honoring the Lord. To my searching mind, this seemed like a hollow, robotic faith. Life, intended to be a wide-ranging experiential symphony, reduced to a single note played over and over again: duty, duty, duty. My freshman year, at one of the very safe parties Crusade threw, a mutual friend had put on Huey Lewis’s “Hip to Be Square” and publicly dedicated it to my brother (“Now I’m playing it real straight. / And yes I cut my hair. / You might think I’m crazy. / But I don’t even care. / ’Cause I can tell what’s going on. / It’s hip to be square”). I just laughed at the song, but later it struck me as apt. My brother had always had this “model citizen” way about him that I resented, but I didn’t yet have the eyes to see that our differences were at core more temperamental than theological. Rules and order and the strictures of faith suited him, gave him an ease with religion that I lacked.

The larger problem I had was less religious than hormonal. I’d fallen hard for a cheerleader at our rival high school who was involved in the Crusade chapter there. Liz, known as “Lizard” or “Reptile” to her friends, was blond, zany, and optimistic, a vision of clean Christian California. Her parents were divorced, like mine—a rare thing in ’80s San Diego—which served to cement our bond. Our romance unfurled in my mind like a Hollywood film.

Because Liz was a cheerleader, she was considered a “key woman” in Jesusland and was expected to be “above reproach,” in accordance with 1 Timothy 3:2 After a group retreat where Liz and I had been spotted briefly holding two fingers together (even in our fervid state we wouldn’t have dared to hold whole hands), she broke the news to me. Her Bible study leader had taken her aside and explained that Jesus had big plans for her and that she wasn’t yet ready for a relationship.

“The Lord comes first,” she explained.

Then, senior year, I got a three-hundred-dollar speeding ticket that required me to quit the football team and get a job at the mall to pay for it. Losing my wonder-boy status had a curiously dispiriting effect on me, and before I knew what was happening, I had failed almost all my classes. I was allowed to attend the graduation ceremony that spring even though I was two classes shy of my degree.

When I walked off the stage and uncorked my diploma tube, I saw that it was empty. Some metaphors write themselves.

In time, I was able to claw my way out of the hole I’d dug for myself. I got a job at a nearby television factory and took remedial math at a junior college. With the credits I earned there, I was provisionally admitted to Texas A&M the next fall and got involved with the Crusade chapter there.

As part of my admissions agreement, I was expected to join the A&M Corps of Cadets, a full-time ROTC program that functioned like a military academy within the larger university. The structure was good for me. My grades rose. For a couple of years, I colored within the lines, dutifully attending a cadet Bible study led by a Crusade staffer who was also a reserve army officer. Then a rather predictable thing happened: My junior year, I took a philosophy class and I began to reconsider my faith. I read some existentialism and started keeping a journal. The seeds of doubt, planted in high school, bloomed.

The disillusionments of high school had tested my spirit but spared my faith, but what finally separated me from Christianity was a growing boredom and a kind of emptiness when I realized that my brother was right—the discipline of faith was the point, not any of the supposed truths of Christianity. Religion is where the irrational meets the political.

My senior year, I enrolled in an intellectual history class, along with Ryan, my best friend from Crusade, where we were introduced to the Antichrist himself, in the form of Friedrich Nietzsche. Nietzsche opened the door to a banquet of questions, and within a year the whole core of my thinking had shifted dramatically. I saw that Christianity was little more than a system of control with a toxic history, not a serious theory about how the universe worked.

I’d been lied to. Worse yet, I’d spread this lie to others, participated in its propagation on an industrial scale. Quietly and without fanfare, Ryan and I stopped attending Crusade meetings and spent our free time reading and discussing philosophy. That summer I reported to Marine Officer Candidates School at Quantico, Virginia. Years later, I would see this for what it was: another coded attempt to prove myself to my family and a way to beat my brother at his own game—in the process distinguishing myself by the mark of martial discipline. We may leave religions, but they don’t leave us. As the psychologist Erik Erikson observed in his landmark 1950 study Childhood and Society, “The individual unconsciously arranges for variations of an original theme which he has not learned either to overcome or to live with” and manages his anxiety by “meeting it repeatedly and of his own accord.”

At the end of my junior year, my brother graduated from UCLA, joined Campus Crusade staff, and departed on a yearslong mission to Russia. Somehow, despite my spirited rejection of Christianity, a residue of shame remained. There was a time when I’d believed in clean getaways, the idea that you could just start over, reboot your existential operating system; but when you give yourself completely to a cause, as I’d done with Crusade, it’s impossible to just walk away. Part of you stays there forever, trapped in the amber of memory.

Nearly thirty years would pass before I told my brother that I was a traitor to the faith.

Back in Jesusland, inside the cavernous Anaheim convention hall for Cru’s 2024 Winter Conference, things had settled a bit. The uplifting music had stopped and a Korean-Mexican-American pastor from Sacramento was up onstage, explaining to us the importance of acknowledging the Lord as Our Father. The pastor was a gifted orator, and I could feel my heart moving in the old holy ways, and I could sense certain questions stirring that I’d long ago dismissed as the province of idiots. Christianity was, as I’d explained to my brother a few months prior, “a moral catastrophe and perhaps the greatest conspiracy ever inflicted on the human race.”

But here in a sea of happy believers, who exactly was I to judge? Like any religion, Christianity was just a dream, after all. Everyone deserves a dream, something to console them when life takes a turn for the worse, something to get them through the night, as Frank Sinatra put it. The questions kept swirling, going nowhere in particular, and when I finally snuck a look at my phone, it was nearly midnight. And yet I wasn’t tired. No one was.

A lot had happened since I’d left Crusade: the internet, social media, Bush, 9/11, Iraq, Trump, the end of Roe v. Wade. The evangelical movement, which had begun as a wholesome American project to spread a stripped-down version of Christianity, had metastasized into a pro-fascist interest group. The resort at Arrowhead Springs had been sold in the early ’90s and Cru’s headquarters relocated to Orlando. Bill Bright had died in 2003, but not before signing off on a final crusade, affixing his name to what became known as the “Land Letter,” a missive sent to President Bush encouraging him to invade Iraq, claiming, with the perverted logic common to all fundamentalists, that God approved of the king’s war. With Bright gone, Campus Crusade began a slow process of rebranding, and in 2011, it changed its name to “Cru,” a move that drew the ire of some conservative Christians, who viewed the deletion of “Crusade” as a concession to those who felt the name was a bit too reminiscent of the actual Crusades, which had resulted in the deaths of millions of Muslims.

Throughout his life, Bright had always insisted that he’d “never been involved in politics,” but looking back on my time in Cru, I could see that this was a lie. At every stage of its history, Cru had championed the conservative cause du jour, creating what amounted to a guerrilla academy for the American culture wars. In the ’50s, the cause had been anti-communism. In the ’60s, it was fighting the antiwar counterculture and sex, drugs, and rock and roll. In the ’80s, Crusade had taken up the cause of “family values,” brainwashing me and my friends about the horrors of premarital sex, abortion, and homosexuality. In the Trump era, Bright’s project continued to bear fruit in the work of the Alliance Defending Freedom, litigating the end of Roe v. Wade in the Supreme Court.

Looking over the 2024 Winter Conference schedule, it appeared that Cru was engaged in the culture wars yet again, albeit in an unexpected way. While the second afternoon of the conference had the traditional “Day of Outreach” to the local community, interspersed between the main sessions were events like a “BIPOC Lunch” and a series of discussion groups aimed at Asian American students. On a nearby table lay books for sale. Indigenous Theology and the Western Worldview: A Decolonized Approach to Christian Doctrine sat next to Redemptive Kingdom Diversity: A Biblical Theology of the People of God, along with other books about how to run an inclusive ministry.

Could it be? Had Cru gone woke?

Later that week, I spoke to John G. Turner, a historian of religion at George Mason University and author of a history of Cru, who explained to me that in the wake of George Floyd’s death there had been some division in Cru over how to respond to the nationwide calls for racial justice. A letter had been sent to Cru’s leadership, demanding change. “I think Bill Bright’s successors have been less interested in public right-wing politics than he was,” he explained. “My sense is that Cru’s leadership attempted to do enough to satisfy those who cared about racial justice without alienating those who reject those moves. And given the current political and theological landscape, that balancing act has become much harder.” It’s difficult to know what Bright would’ve made of Donald Trump, though Bright had no problem with Richard Nixon or the American war in Vietnam, and it’s likely he would’ve found a way to support Trump, as most evangelicals have.

They say the personal is political. Ask any Marine who lost his legs in Iraq, or a pregnant fifteen-year-old girl in Texas. For me, there was never an opportunity to unlearn Cru’s political system and its claims on my body. I never discovered how to rewrite my emotional software. To this day, romance carries with it the stain of sin, an echo of Liz, a lingering expression of what Robert Jay Lifton called the “shaming milieu.” When you’re programmed as a kid to believe that physical intimacy is literally the devil’s handiwork, you don’t just wake up one day and have a healthy sex life. I scarcely dated in college, fearing the reproach of an invisible Bible study leader. I never married.

My plan in coming to the conference had been to do a sort of reconnaissance, to get a sense of how Cru had changed by standing back and watching. And yet here I was, singing and clapping along like the collegiate believer who had long since passed away. As I would learn later, talking with some staffers, Cru had undoubtedly changed, its politics tacking with the winds of the zeitgeist for once, but its ability to draw people to Jesus and make them feel accepted and loved hadn’t changed at all. Driving the music was the same beat I’d heard on that San Diego beach decades before, that singular commandment stamped on the drumhead: Belong. Belong. Belong.

I turned to the woman sitting next to me, whom I’d met earlier in the evening: an Oregon State senior named Ava, majoring in psychology. Ava, it turned out, was going to grad school the next fall to become a Christian counselor. Driving to Anaheim, I’d assumed that I’d be greeted with suspicion and maybe even asked to leave. But Ava and all the students I talked to all had such warmth. It just flowed out of them like a holy pheromone.

“What are you hoping to get out of the conference?” Ava asked.

The two of us chatted for a few minutes, eventually exchanging prayer requests, a transaction that was for me both an obvious lie and a charming gesture at the same time.

An unmarried academic in a big American city, I’d forgotten that community could be so easy. In a time of social rupture, an era dominated by distrust and skepticism and paranoia, I could feel my heart melting. It struck me then that the name change to Cru, i.e., “Crew,” was apt. On some deeper level, I knew this was a nostalgia ambush I was undergoing, not a rebirth of faith, but why not enjoy the reverie, I reasoned, and see where it led? Sure, Cru had hijacked my youth and stolen my sexuality, but now wasn’t the time to dwell on such matters. I have always been a soldier of memory, and I knew I would go back and count the costs, replay the scene.

A few minutes later, the music stopped. The house lights came up. It was time to go, the reverie over. I walked back to my hotel room alone, my steps still marking the beat. A seductive lie in the form of a code, still broadcasting after all these years and likely to call out forever and ever, amen: Belong. Belong. Belong.