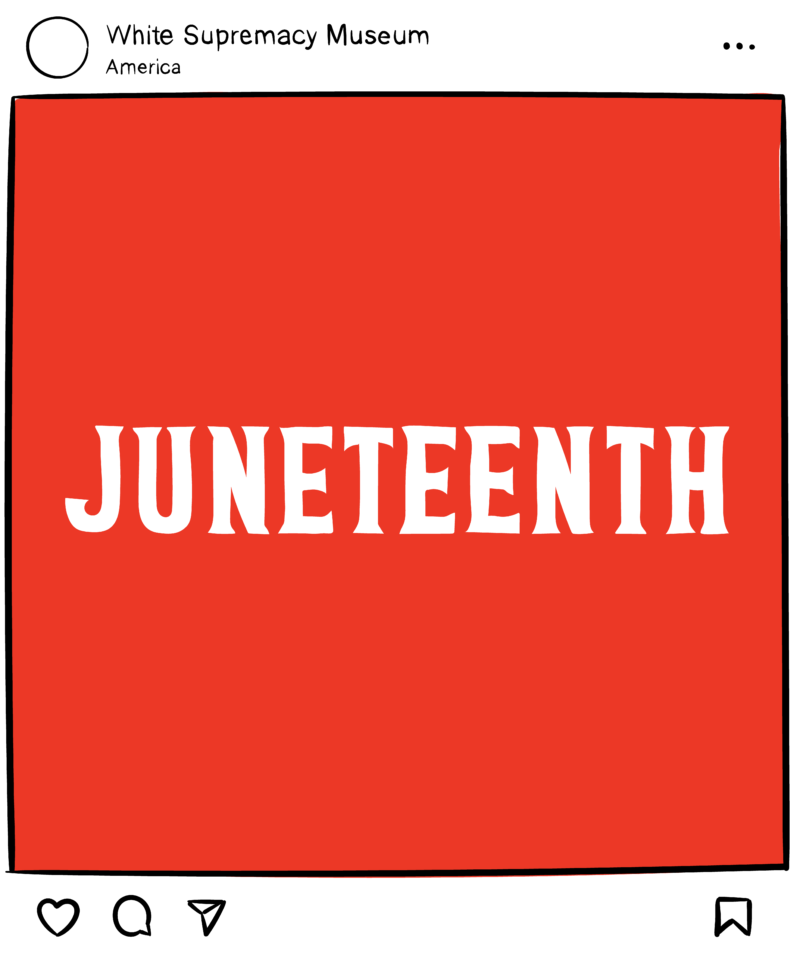

On June 19, 2020, almost every major museum in the United States issued a social media post addressing Juneteenth, the holiday marking the emancipation of enslaved men and women in Texas. Despite the faithful celebration of the holiday among Black communities since 1865, prior to this moment, few, if any, mainstream museums had acknowledged the holiday. In the weeks leading up to Juneteenth, we anticipated that, for the first time in our decade-long careers as Black museum professionals, museums would recognize their responsibility in acknowledging this seminal moment in Black liberation.

George Floyd was murdered on Memorial Day 2020, and in the aftermath of Black Lives Matter (BLM) demonstrations to seek justice for him and other high-profile victims of racial violence, the significance of Juneteenth suddenly shifted in the national consciousness and spilled into the ever-white museum landscape. There is a horrifying and heartbreaking poetics to the interconnections between George Floyd’s murder on a day of remembrance; the subsequent public (re)dedication to BLM, abolition, and liberation projects in his name and those of many others; the way BLM protests folded in critiques of museums and monuments; new interest in a holiday recognizing Black freedom; and the superficiality with which museums, institutions dedicated to memory preservation, attempted to allay protesters through tepid diversity commitments.

Many of these museums, in some capacity, begrudgingly began to consider their complicity and active participation in Black oppression and death. For while these institutions claim neutrality and promise progressive advancement, it is the fallacy of these claims that led them to believe Juneteenth posts had not been their responsibility prior to 2020, and then suddenly were their sole responsibility in summer 2020. Though the bulk of museum statements in support of BLM were released in summer 2020, and despite the subsequent influx of articles and virtual events exploring the racial problems of museums, we made a conscious choice to write this article now, in these events’ aftermath. Our timing illustrates the need for a pause, a real moment to recalibrate, reconsider, and bear witness to the inaction that succeeded those statements. So here, let us sit with the violence embedded in museums—institutions that were founded as champions of whiteness and repositories for European colonization (how else to describe institutions like the Louvre and British Museum?). We, as Black museum professionals, critique this history, but that is not enough. How do we envision changes that truly make room...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in