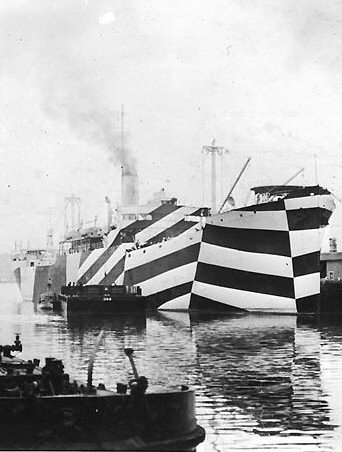

USS Mahomet in port, circa November 1918.

Camouflage was designed to hide things, but how it changed our worldview may be its most revealing surprise. This five-part series examines the history of camo, from its humble origins to its current ubiquity. Catch up with Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, Part V.

PART THREE: Guile and Ghillie

It wasn’t cost-efficient during World War I to mass-manufacture camouflage fabric—it was all hand-painted. That mind-boggling fact explains why most soldiers wore solid drab uniforms in World War I. Camouflage crept into the ranks as sharpshooter garb, conveying elite status in much the way drab originally did.

The Germans decorated their special-issue Stahlhelm (steel helmets) in a crisply disruptive pattern; trench-assaulting storm troopers wore these starting in 1916. Less romantically, “ghillie suits” worn by snipers turned them into walking shrubs. (The name stems from a Gaelic term for landowner servants who hid in wait to snag poachers.) Disruptively patterned ghillie bodysuits came with matching balaclavas and three-fingered mittens (to accommodate the trigger finger); soldiers stuck greenery into the fabric to complete the ruse. The look perfectly combined a Klansman-like severity with a certain hangdog awareness of how ridiculous one looked when removed from his perch. Still: hot, inconvenient and mockable as they were, a good ghillie suit really worked.

Sea and Air

In 1917 German U-boats successfully torpedoed 23 British ships weekly—55 during one week in April alone. British Lieutenant Norman Wilkinson’s solution, “dazzle” camouflage, ushered in a newly visible era for camo. Wilkinson described his insight in his autobiography:

…Since it was impossible to paint a ship so that she could not be seen by a submarine, the extreme opposite was the answer—in other words, to paint her, not for low visibility, but in such a way as to break up her form and thus confuse a submarine officer as to the course on which she was heading.

Submarine shooters needed to estimate a ship’s direction, speed and location to calculate where to shoot. Dazzle, it was hoped, would throw off these estimates, increasing the odds a torpedo would miss its target.

Allied Navies took to dazzle keenly, testing patterns on miniature boats in simulated conditions before daubing up a fleet. Airplanes sported countershaded undersides to blend into the sky, while their dazzled tops stood out in a confusingly artful way.

Dazzle paint wasn’t even the most outlandish idea for hiding ships. Thayer tossed out numerous ideas: an all-white Allied fleet that attacked only at night, schemes for giant concealing nets or tarps daubed with clouds. Others proposed disguising ships as whales or hiding them with mirrors. Thomas Edison wanted to conceal ships as floating islands; Douglas Volk suggested shrouding them in mist pumped from angled pipes—an idea tested in 1996 to conceal the British warship Sea Wraith’s heat signature.

Disrupt and Dazzle

Did camouflage work in World War I? Disruptive patterning did reduce one’s visibility, although Allied calculations of camouflage’s overall return on investment were clouded by the overwhelming reality of victory.

Dazzle offered the shakiest evidence. FDR decried dazzle as “Juju black art bad man no can see”—which didn’t stop the U.S. Merchant Marine from painting its entire fleet in dazzle in 1916. Post-World War I studies offered only mixed proof of dazzle’s effectiveness. Where dazzle and camouflage were unquestionably effective was in morale. A 1918-era song describes dazzle as evidence of the Allies’ wit—the newfangled cleverness that won the war:

Captain Schmidt at the periscope

You need not fall and faint,

For it’s not the vision of drug or dope,

But only the dazzle-paint.

And you’re done, you’re done, my pretty Hun.

You’re done in the big blue eye,

By painter-men with a sense of fun,

And their work has just gone by.

Cheero!

A convoy safely by.

In World War I’s aftermath, dazzle symbolized victory, jazz, and the layered sophistication of a triumphantly mechanical age. Here’s the London Times describing a dazzle-themed ball in March 1919:

“Here it seemed was a token, unmistakeable if bizarre, of some of the things which the dark years had achieved…To the strains of the Jazz band these amazing revelers, vanishing and reappearing, seemed to set at naught the world of the past and all the portentousness of it. They hailed a new world, swifter, gayer, more adventurous.”

It’s a fittingly rich irony: the pattern that boldly hid ship convoys now clad the Lost Generation.

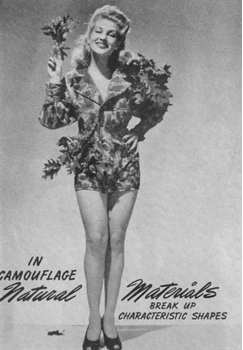

British bathers in The New York Tribune, June 1919. From Roy Behrens collection.

Camo’s heyday

The increasing threat of aerial attacks meant that even doubters got back into camouflage in the ramp-up to World War II. With the notable exception of dazzle, all the camo-tactics of World War I were expanded, including training. Over-enthusiastic civilians and troops could produce eye-catchingly bad camouflage—“like a Macgregor tartan at a Brixton funeral,” as one scholar puts it—suggesting a pressing need for education.

A shower of booklets, posters, and flyers explained what effective camouflage looked like, using every tactic to grab their audience’s attention. Surrealist painter (and British camoufleur) Roland Penrose spiced up his training slideshow with a naked image of his wife Lee Miller, smeared in camo-paint and tangled in netting. A U.S. Army training manual featured pinup girl Chili Williams in a camo-themed series that ran in LIFEMagazine.

The Win Column

Camouflage played a front-and-center role in two Allied wins: El Alamein in 1942 and D-Day in 1944.

At the Second Battle of El Alamein, the Allies prevented German commander Erwin Rommel from seizing the Suez Canal and Mideast oil reserves. The Allies staged a fake supply buildup south of El Alamein, replete with inflatable tanks and phony artillery flashing. British camoufleur and stage magician Jasper Maskelyne helped pull off El Alamein’s most audacious feat: hiding the entire Suez Canal from aerial view with a combination of mirrors and massive searchlights. (Hiding waterways was easier than it sounds: a mixture of coal dust and fuel oil would float on still water and reduce the water’s shine.)

Just before D-Day, Allied troops seemed to be amassing in Scotland and Kent to attack Norway, while actually concentrating forces aimed at Normandy. Movie studios helped construct a head-spinning number of false oil storage tanks, landing jetties, and inflatable tanks, while creating blinds to cover real troop buildup. The ruse continued after landing in France with the 603rd Engineer Camouflage Battalion of the U.S. Army. This “Ghost Army” took the place of the actual U.S. battalion marching stealthily to Normandy. The Ghost Army included several camoufleurs bound for fame, including artist Ellsworth Kelly, fashion designer Bill Blass, set designer and actor George Diestel and Ed Haas (co-creator of The Munsters).

Jude Stewart writes about design and culture for Slate, the Believer, Fast Company, and Print, among other publications. Her first book ROY G. BIV: An Exceedingly Surprising Book About Color is now available from Bloomsbury. Follow her on Twitter @joodstew.